Richard was the youngest of Andrew Bent’s known siblings and the last of the three Bent brothers to be transported. Like his two older brothers he had a useful trade. Like them he put his unfortunate London background behind him and turned over a completely new leaf. Perhaps assisted by the prosperity and standing already acquired by Andrew, he built a modest business success and stayed out of political trouble. Yet there is a sting in the tail of Richard’s story. He and his wife Ann came badly unstuck in the end.

London to Sydney 1797-1822

Richard arrived in Sydney on the Earl St Vincent in August 1820. All 160 male convicts were landed in good health after a relatively uneventful voyage.

In January 1820 Richard had been convicted (under the alias of William Wood) of possession of forged notes. He was tried as a job lot with a number of others. All pleaded guilty to possession thus avoiding conviction on the capital offence of disposing. All received sentence of fourteen years’ transportation.

Richard had already been in trouble with the law. Four months earlier, in September 1819, he was convicted (under his real name) of fraudulently obtaining a piece of linen. For this he received a whipping. Newgate records for these two convictions describe him as 21 or 22 years old, a bricklayer by trade, whose native place was Drury Lane.

Andrew may have kept in touch, describing how he had fallen on his feet in Hobart Town. Although we cannot be sure, it is just possible – especially as middle brother Benjamin had also been shipped off to the colonies by 1819 — that Richard was actively courting transportation.

Richard probably learned his trade as a pauper apprentice. In February 1811, while Andrew languished in Newgate under sentence of death, Richard Bence, a poor child of the parish of Saint Giles, aged twelve, was apprenticed to Charles Stanley Masterman, bricklayer, of Bethnal Green. It must have been hard work for a fellow who, even in adulthood, stood half an inch short of five feet and was later said to be, like both his brothers, ‘awkwardly made’.

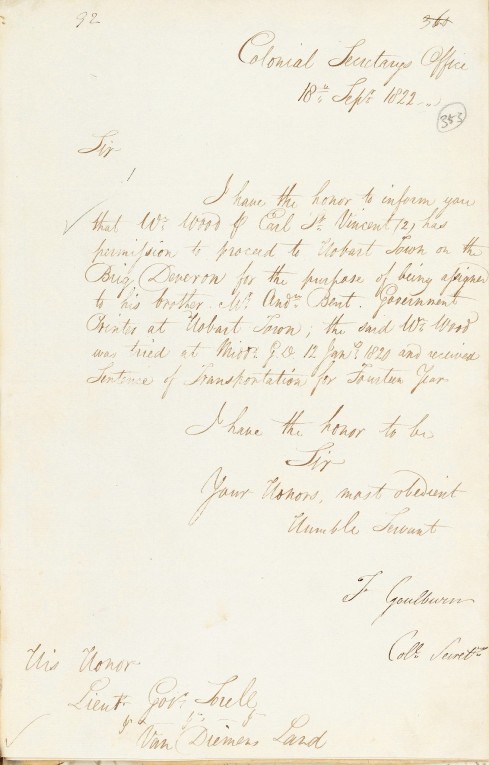

After arriving in Sydney William Wood worked as a government bricklayer during 1821 and early 1822. Andrew must have known he was there, for in September 1822 William Wood was permitted to proceed to the Derwent to be assigned to his brother, Andrew Bent. New type and printing presses were on their way out from England. Andrew had plans for a purpose-built printing office to house them and a bricklayer brother could save him some serious money.

Hobart Town 1822-1836

Assignment

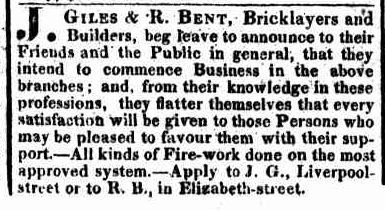

The two story brick printing office, with walls 14 inches thick and a dry cellar 18 by 40 feet, was finished by the end of November 1823. Richard then took advantage of having arrived quietly under an alias and, using his real name, immediately announced a business partnership with bricklayer Joseph Giles. This arrangement, obviously condoned by Andrew, occurred well in advance of Richard’s ticket of leave in 1826.

Jorgen Jorgenson, who did not arrive in Hobart until 1825 but always had an ear for gossip, claimed that Andrew treated Richard badly during his period of assignment. He frequently threatened him with punishment, and refused to allow him to eat at the same table. The three brothers hardly ever spoke to one another and Jorgenson had personally heard them call each other ‘d—-d rascals.’ There may have been some truth in these comments although Jorgenson was writing with an obvious agenda to undermine Andrew’s petition to the House of Commons (1836). Shortly afterwards Gilbert Robertson spitefully went much further – insinuating that ‘Little Twopenny’ (Andrew) had barely shaken the shackles from his own legs when he had his brother flogged. This was quite untrue, as demonstrated by Richard’s completely clean conduct record, but somebody obviously knew, possibly from Richard himself, that his back bore the marks of the lash.

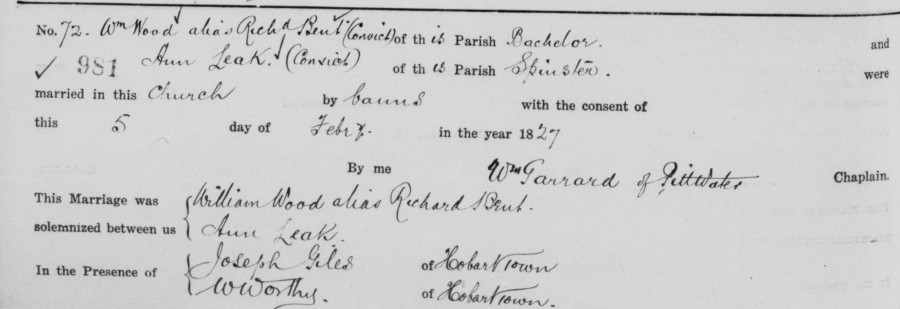

Marriage

On 5 February 1827, with his friend Joseph Giles as a witness, Richard married Ann Leak, a Lincolnshire lass about eight years younger than himself. Ann, who had grown up in the little village of Billingborough, was very slightly taller than Richard, with a fair complexion and dark hair and eyes. Like Richard she was literate, but not highly so.

Ann had arrived on the Midas in November 1825 under a 14-year sentence for stealing from her employer – a draper in nearby Sleaford. Given her youth (just eighteen) and previously unblemished character she might have expected a short custodial sentence but, just as the trial was about to conclude, things went badly awry. Under pressure from the judge to say something before he passed sentence, Ann blurted out what may well have been the truth – that she had been seduced by her employer. Later documents variously suggest that he told her she could take the items, or that she took them because he reneged on a promise to buy her silence about their dalliance. This unexpected introduction of new matter greatly irritated the judge. The draper made a solemn denial and Ann – deemed to have made a wanton and lying attack on the man she had robbed – received a very severe sentence. She and her family were terrified at the prospect of transportation and nearly everybody in the village signed a petition on her behalf. This was unavailing, as were several long and eloquent letters from a Lieutenant General Loft (a man of dubious character in gaol for debt) who assisted Ann, probably for a fee.

For almost the entire voyage Ann was treated for sea sickness, headache and bowel complaints. Whether she was genuinely ill, malingering, or simply overcome with fear is not clear, although she seemed to make a full recovery a couple of days before the ship arrived in Hobart. The surgeon, obviously a kindly and conscientious man, may have simply been keeping her safe.

For at least part of her sentence Ann was assigned to Andrew Bent’s former editor H. J. Emmett where one assumes she was well treated. Her conduct record, like that of her husband, is spotless.

Business success

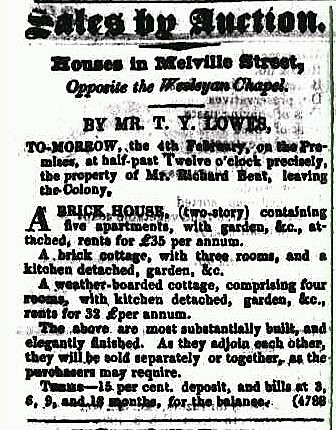

Richard was sober and steady, concentrating on building up his business and steering well clear of the local politics which embroiled Andrew. From 1827 he is listed in various almanacs as a bricklayer in Melville Street, opposite the Wesleyan Chapel. He occupied a weatherboard cottage on a block owned by Andrew which had been on the market sporadically for some time.

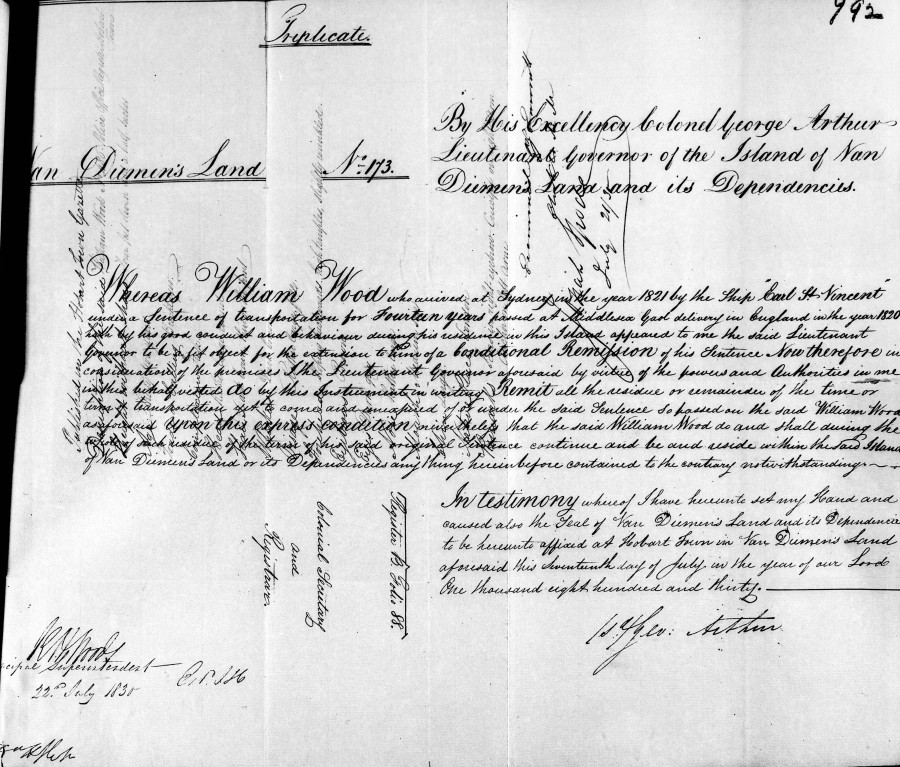

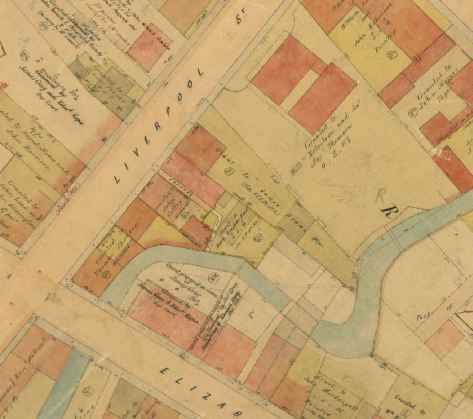

As well as doing paid work, at times in partnership with Joseph Giles and later with James Webb and John Allee, Richard operated as a successful spec builder. He bought the Melville Street property from Andrew in 1828, although the deed was not lodged until after Richard was conditionally pardoned in 1830. He later used this property – for which he had paid £70 – as security for a £200 loan from Henry Hopkins. He acquired an adjoining block and erected a three roomed brick cottage and a two story brick house. He sold the whole development for a substantial profit just before the downturn in Hobart property prices which so adversely affected his brother. He had an interest with Andrew in a property in Brisbane Street which they sold in 1830 and was probably the builder of the brick house on it. He had a similar interest in a Liverpool Street property with his friend James Brown (of which more later). In 1833 he advertised to let a ‘neat Brick Cottage, containing five rooms, eligibly situated in the centre of the town.’

When Richard applied for a conditional pardon in 1830 he was strongly recommended by Edward Abbott Junior, JP and ‘other respectable persons.’ The description on his pardon shows he had changed little in the ten years since transportation, although his hair was now receding further from a high forehead, and dark brown whiskers covered what had earlier been described as a ‘slightly pock-pitted’ face. He sported two tattoos.

Richard was possibly a member of the Wesleyan congregation and gave modest amounts to various charitable causes. In the 1830s his property qualified him for the jury list. After he became free he was entitled to convict workers, one of whom was flogged for insulting and disrespectful conduct towards him. In 1833, he and the before-mentioned James Brown applied unsuccessfully for a licence as pawnbrokers. Brown, presumably as the more literate of the two, wrote the letter, but struggled with his spelling.

Departure

Early in 1835 Richard, stating he was leaving the colony, advertised his Melville Street properties for sale. His sentence had by this time expired and Ann had been recommended for an absolute pardon. Her marriage to a ‘well conducted man’ counted in her favour. They had no children to tie them to Hobart and once Ann’s pardon was confirmed wasted no time in quitting the colony. On 14 May 1836, just three weeks before the town was thrown into uproar by the announcement of Governor Arthur’s recall, they sailed for London on the Derwent. It looked as though they were leaving Hobart Town for good.

England and Sydney 1836-1839

The Derwent arrived in London on 12 September 1836. Whatever their original plans may have been, they did not stay long. While in England they probably visited Ann’s family in Lincolnshire. Curiously, although they were already legally married, they had their banns read three weeks running at Saint James, Clerkenwell. It seems however that no marriage ceremony ever took place.

They were probably the Mr. and Mrs. Bent who arrived in Sydney on the Hebe in June 1837, just a year or so after leaving Hobart Town. Nothing is known of their time in Sydney apart from their departure for Adelaide just eighteen months later. The timing is very interesting. They sailed on the John Pirie on 27 February 1839, only three days before Andrew, with little money and ten children, arrived in Sydney hoping to make a fresh start – surely no coincidence!

Adelaide 1839-1845

Richard’s sojourn in Adelaide as bricklayer and builder is documented in various directories, advertisements, newspaper reports, property records, and in the 1841 census. He spoke at a public meeting about a new bridge, advocating the power of newspaper publicity. He signed an address to Governor Gawler. He received a grant of land in the Barossa and acquired a property in town at the western end of Hindley Street. He appeared to be a man of some substance when, early in 1842, he advertised his intention of retiring from business and going to England. The two properties were for sale, as well as handsome household furniture, a horse and cart, a splendid tool chest, box of mathematical instruments and even a ‘choice library.’ The lavishly described Hindley Street property did not sell despite having a two story brick house, large brick stable, elevated position and beautiful views.

In September 1843 Richard conveyed both his town properties to Joseph Roberts in trust for Ann. The reason for this is not altogether clear but perhaps his business was feeling the effects of the depressed times and he wanted to safeguard his assets by placing them in his wife’s name. Then there occurred two very curious transactions. In late February 1844 the trustee sold them both to shoemaker Tom Cox Bray for £150. Just three months later, in May, Richard paid Bray £200 to buy them back again!

What on earth was going on? Was it connected to the prosecution (over a dishonoured bill of exchange) which the Bank of Australia brought against Richard at around this time? The case was touch and go but the court eventually found in Richard’s favour. Or could it be related to events concerning Ann which made shocking reading in the Adelaide newspapers?

Mrs. Bent’s disgrace

On 2 March 1844 two policemen arrived at the Bent house with search warrants. They were afforded every assistance by Richard. In an outhouse they found a pillowcase stuffed with stolen property – shawls, a fan, a card-case, an apron, lengths of crepe and some veils. There was an eerie resemblance to the items Ann allegedly stole in Lincolnshire nearly twenty years previously. Ann confessed to taking the goods, attempted to bribe the police to hush things up and begged them not tell her husband. Most items had been taken from the house of a nearby solicitor with whose wife she had been on intimate visiting terms. The veils had been removed from bonnets left in the supper room during a social function. Richard, giving a very convincing performance, denied all knowledge of the thefts and beat his breast about how his wife had disgraced him for ever. He was released. Did he know something was up and had he prepared his affairs accordingly? And why did Ann do such a thing after being so law abiding for the last twenty years. All she could offer by way of explanation was that the temptation was too great.

Ann was committed for trial and lodged in gaol on 3 May. She applied for bail on the grounds of extreme ill health but this was refused. At her trial in July she pleaded guilty. A number of character witnesses said they had known Richard and Ann for some years as a most respectable couple. Despite this Ann was sentenced to a total of eighteen months imprisonment, with hard labour ‘such as she can bear’ and three two-week stints of solitary confinement.

The gaol was newly constructed but conditions were harsh. The Governor, William Baker Ashton, was a kindly man with a difficult job to do. The few women prisoners were noisy and quarrelsome and resented the presence of two mad women who were confined in the gaol for want of anywhere else to house them. In October one of these, Mary Rhodes, was released from her straitjacket to wash and ‘very much beat Mrs Bent about the face,’ as Ashton relates in his journal. Ann was still being seen by the doctor a week later.

Ann spent a miserable Christmas in solitary confinement and late in January petitioned Governor Sir George Grey for remission of her sentence. Expressing deep contrition, she described the debilitating effect of her confinement on ‘an already delicate constitution.’ The bleeding treatment given by the doctor had probably not helped her. Richard’s health had been suffering too. Ann’s petition was supported by a dozen or so neighbours and friends. She was also recommended by the Sheriff, who noted her fragile health and the ‘rather severe injury’ she had sustained.

All Grey would concede was a remission of the remaining periods of solitary confinement. He undertook to re-examine the case after Ann had served a full twelve months. He was equally unmoved by another application in May. In this Ann related how Richard had been ‘so harassed and perplexed by my wretched position that he [was] quite unable to attend to Business and our little property is dwindling to nothing.’ Both town properties had indeed been sold nearly a year before, the Chief Justice visiting the gaol so Ann could sign the papers. Pre-existing debts were probably exacerbated by legal fees.

Epilogue

On 5 July 1845 Ann was released after serving one full year. Three months later the diminutive and now aging couple slipped quietly away on the barque Guiana bound for Mauritius. Twenty years later, in 1865, Richard’s nephew Andrew Bent junior (of Geelong) placed an advertisement in the Adelaide newspapers. Marking it ‘important’ he offered a handsome reward for the address of Richard Bent, ‘a brewer and builder in Adelaide in 1840.’ I have been unable to trace Richard and Ann beyond Mauritius, so I do wonder if Andrew ever received a reply.

Legacy

Richard and Ann were typical of many convict couples who turned their lives around in Van Diemen’s Land and made a modest contribution to the development of the colony. But they left no direct descendants to remember them. The brick printing office was demolished in 1913 (perhaps earlier) and government office buildings now stand opposite the old Wesleyan chapel in Melville Street. I assumed that all other traces of Richard’s work as a builder had likewise disappeared.

Then, almost by accident, I learned of John Short and his research into the history of the Bank Arcade building in Liverpool Street. This stands on the block once owned by James Brown. In 1832 the property was conveyed to Brown by Mary Frost, in return for an annuity payable to herself and her partner Martin Timms, a former Provost-Marshal, who was by then aging and down-at-heel. Richard was clearly involved in the transaction. He undertook to re-convey the property to Mary Frost if Brown defaulted on the payments. In 1848 Brown claimed the grant prior to selling the property. He stated it had been conveyed to Richard in trust for himself but there was no mention of Richard’s current whereabouts.

John’s painstaking research has shown that a building existed on this block in Hobart’s very early days (from about 1806) and has been modified several times. The current building, dating from the 1860s, retains materials and some of the structure from the original building and also from a rebuild done in the early 1830s by Richard. At this time the original wooden structure was converted into a two story brick building and realigned to face Liverpool Street rather than the rivulet. It was a great pleasure to meet John on one of my trips to Hobart and to see some of Richard’s surviving work.

Further reading:

Harris, Rhondda. Ashton’s Hotel: The Journal of William Baker Ashton, First Governor of the Adelaide Gaol (Mile End, SA: Wakefield Press, 2017)

Short, John. ‘The History of the Bank Arcade Building Site in Hobart, Tasmania, from 2014 to 1804’, THRA Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 62, No. 2, Aug 2015: 2-17.

Short, John. A Different View of Hobart: Peeling Back the Layers of the Bank Arcade Building (Hobart: Quinary Investments, 2020). Chapter 5. Bent and Brown.

Once again a fascinating post! Thank you! Do you know if Richard had any contact in Hobart with his other brother Benjamin? Eve Almond >

LikeLike

Not a lot that I know about Eve. However my first sighting of Benjamin in Hobart is when he witnessed the dissolution of partnership between Rickard and Joseph Giles on 1 Sept 1827 (HTG 8 Sep 1827). And Benjamin’s owned a property in Brisbane Street which was next door to the one which Andrew and Richard sold in 1830.

LikeLike

Congratulations Sally. A fantastic well written piece.

LikeLike