George Clark was Andrew Bent’s predecessor as Government Printer in Van Diemen’s Land. His time as a printer in Hobart Town, from around 1810 to 1815, was relatively short and he has been largely forgotten and overshadowed by Bent’s own later achievements (and self-promotion). Clark was obviously a less skilled printer than Bent, but he must be given credit for printing the first two newspapers in Van Diemen’s Land, as well as the earliest surviving book printed in the colony. Clark was also one of Hobart’s very earliest convicts.

Conviction/transportation

George Clark was, like Bent, a London burglar. At the Old Bailey Sessions House on 4 July 1798 the 25 year old Clark (recorded as Clarke) and James M’Nell, 28, were tried for housebreaking. At about four in the afternoon of 3 June they allegedly entered a dwelling-house near London wall while the occupants were out and stole goods worth over eleven pounds – six teaspoons, a pair of sugar-tongs, a pair of shoe buckles (all silver), a pair of shoe latchets and various articles of clothing – as well as two guineas in money. They appeared to be at least semi-professional burglars, based on the quantity and value of the loot and M’Nell’s acquittal on a very similar charge earlier in the year. Clark lodged in Cow-heel-alley, Golden-lane – a ‘deplorable place to see’ – where, in a closet under the stairs, various burglar’s tools were found – ‘a broken crow[bar], a large gimblet, and a false key for taking impressions off.’ Traces of wax were still present on the key. Although Clark claimed to have been dining with his uncle at Islington at the time of the robbery, both men were found guilty and sentenced to death.

Clark’s prison records describe him as five feet five inches tall, a native of London, and a printer and engraver (possibly engineer) by trade. There is no record of him being apprenticed through the Stationers’ Company. Shipboard companion William Noah referred to him in his journal as a watch-case maker. Clark may have been married. The trial report mentions his sister in law living in the same house. Clark walked with a limp, or at least he did by the time Jorgen Jorgenson knew him in Hobart Town, where he was known as ‘lame or hopping Clarke.’ A letter written in 1817, probably in his own hand, shows him to be quite literate, with good handwriting and spelling.

Both culprits were respited and transported for life on the Hilsborough. They were spared the horrors of the hulks, but were lucky to survive the seven month voyage on a ship ravaged by fever. The Hilsborough had the worst death toll in the whole of transportation history. Ninety-five out of the three hundred convicts who embarked died on the passage. The survivors were landed in July 1799, sick and nearly naked. An obviously shaken Governor Hunter described them as ‘the most miserable and wretched convicts I have ever beheld.’

M’Nell (sometimes recorded as McNeil or other variant spellings) fell on his feet. By 1806 he was conditionally emancipated and working for Simeon Lord in Sydney. Clark, meanwhile, for reasons that are not clear, was sent to Van Diemen’s Land. He arrived in November 1803, as one of a party of convicts sent to augment John Bowen’s recently established settlement at Risdon Cove. In April 1804 he was transferred to the Sullivan’s Cove settlement.

He is recorded in the 1803-04 victualling book in receipt of food and clothing. In 1810 he married Elizabeth Fox. Both were recorded as single. According to the Australian Biographical Database Elizabeth was from Lancashire and had been transported on the Experiment, arriving in Sydney in 1804 and possibly transferred to Hobart in 1805 but there is no further definitive information about her. At the 1811 Hobart Town muster Clark was recorded as a convict still under sentence.

Early printing

Clark probably did not work as a printer on first arrival. The earliest printing in Hobart Town, comprising only government orders and notices and done on the small hand press brought out by David Collins, is thought to have been performed by Calcutta convicts Matthew Power and Francis Barnes. Both these men were printers by trade. Power was obviously still in charge of the printing in April 1809 when deposed Governor Bligh, lurking at the Derwent, wanted to print a proclamation, and was told the ink had mysteriously disappeared. While we cannot be sure, it is likely that Clark stepped into the role of printer after Power returned to England, which occurred, according to Marjorie Tipping, in 1809 – obviously after April.

A few early Van Diemen’s Land printed government notices survive in various repositories. These documents do not bear the printer’s name so it is impossible to determine who actually printed them. A proclamation on the bushrangers issued on 11 March 1813 would have been printed by Clark, but the original has not survived. Clarke may have been responsible for all or some of the following:

- Two notices from late 1809 and early 1810 while Bligh was at the Derwent (in Mitchell Library ML MSS 700; noted by Ian Wilson)

- Several notices from 1814 in the Royal Society Collection in Hobart (RS 69). Bent also possible.

- A few more notices and proclamations from around the time of the bushranger crisis of early 1815. These, in the National Archives, Kew, display a mishmash of styles and skill. These could have been printed by either Clark or Bent (or possibly both).

The Derwent Star

January 1810 saw the appearance of Hobart’s first newspaper, The Derwent Star, and Van Diemen’s Land Intelligencer. Two numbers only of this short lived venture survive, and both bear Clark’s name as printer. According to Bonwick the first issue was on 8 January and there were about a dozen issues altogether. A footnote in John West’s History of Tasmania (1852) states the paper was ‘printed by J. Barnes and T. Clark’. This has caused considerable confusion, leading some later writers to conclude that T. Clark must have been Thomas Clark, who was a superintendent and storekeeper under David Collins. West’s note is puzzling. He obviously saw several copies of the newspaper and made extracts from them, yet both the surviving copies clearly state they were printed by ‘G. Clark’. Perhaps West’s footnote is a misprint, or represents a misprint on one of the original issues.

In 1829 John Pascoe Fawkner, who was on the spot in Hobart in 1810 and would have known everybody, clearly identified the printer as George Clark, and the editor as surveyor George Prideaux Harris (see his remarks in the Launceston Advertiser). Fawkner’s reminiscences written late in life add further confusion, stating that the paper was ‘composed and printed by T. Clarke, a printer’ although the rest of the paragraph, mentioning both Barnes and Bent, makes it clear that he is referring to George Clark.

Andrew Bent’s 1829 almanack described the Derwent Star as ‘a little newspaper, containing half a sheet of foolscap, printed on both sides … for a few weeks, by Messrs. Francis Barnes and George Clark.’ It is interesting that Bent, who arrived in Hobart early in 1812, names Barnes first.

In 1861 a copy of the fourth number from the library of Joseph Hone was auctioned in Hobart. It has since disappeared without trace. The Mercury gave a description of its contents, stating that it was printed on ‘two pages little larger than post letter paper’ with the date misprinted as Tuesday, February 20th, 1801.

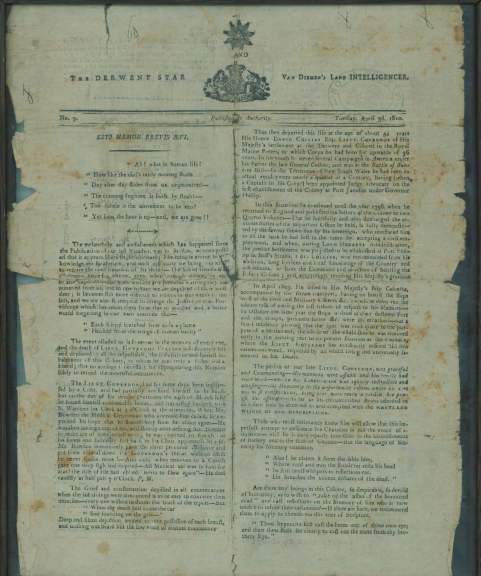

The earliest surviving issue of the Derwent Star is no. 7, dated Tuesday April 3d 1810. This is printed on a single royal quarto sheet with broad margins, and entirely taken up with an account of the recent death and funeral of David Collins. There are three surviving copies, now in the Mitchell Library, the Royal Society collection at the University of Tasmania and the Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne. A number of so called facsimile copies were printed and sold by the Mercury in 1873. The digitised copy on Trove is one of these.

A copy of no. 9, obviously printed in the second half of July 1810, was taken to Sydney by Edward Lord, who was temporarily in charge of the settlement after the death of Collins. This would appear to be the last number of the original series to be mentioned anywhere. On 1 September the Sydney Gazette made some extracts, noting the arrival of Hobart’s new Commandant John Murray and the execution of two malefactors. It observed

The production of a periodical print in an infant Sister Settlement must convey to the mind a strong idea of its rapid progress, and of the energy of our liberal Government in countenancing and supporting such exertions as are laudable and beneficial in their tendency. The Derwent Star is a neat publication, printed every fortnight on a Quarto size. It contains the Government Orders, and various articles of intelligence, of the style of which the above will serve as a specimen, together with some advertisements. To the public patronage it peculiarly lays claim, as a medium of information devoted to the public use; but unfortunately its limited circulation cannot promise any very considerable advantage to those engaged in it.

The paper sold for ten shillings per quarter, or £2 annually, with single papers two shillings each. Copies could be ordered through the Sydney Gazette Office.

The copy of no. 7 now in the Royal Society collection in Hobart (pictured above) was later described by the Mercury as ‘most vilely printed.’ But although it has suffered the ravages of time, and shows the limitations of the press and types with which it was produced, it has few printer’s errors.

New edition

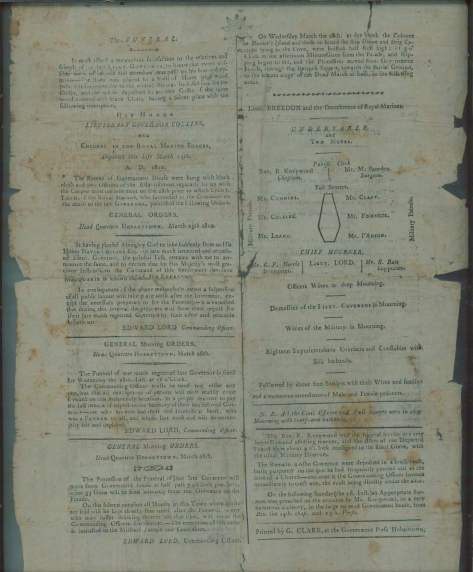

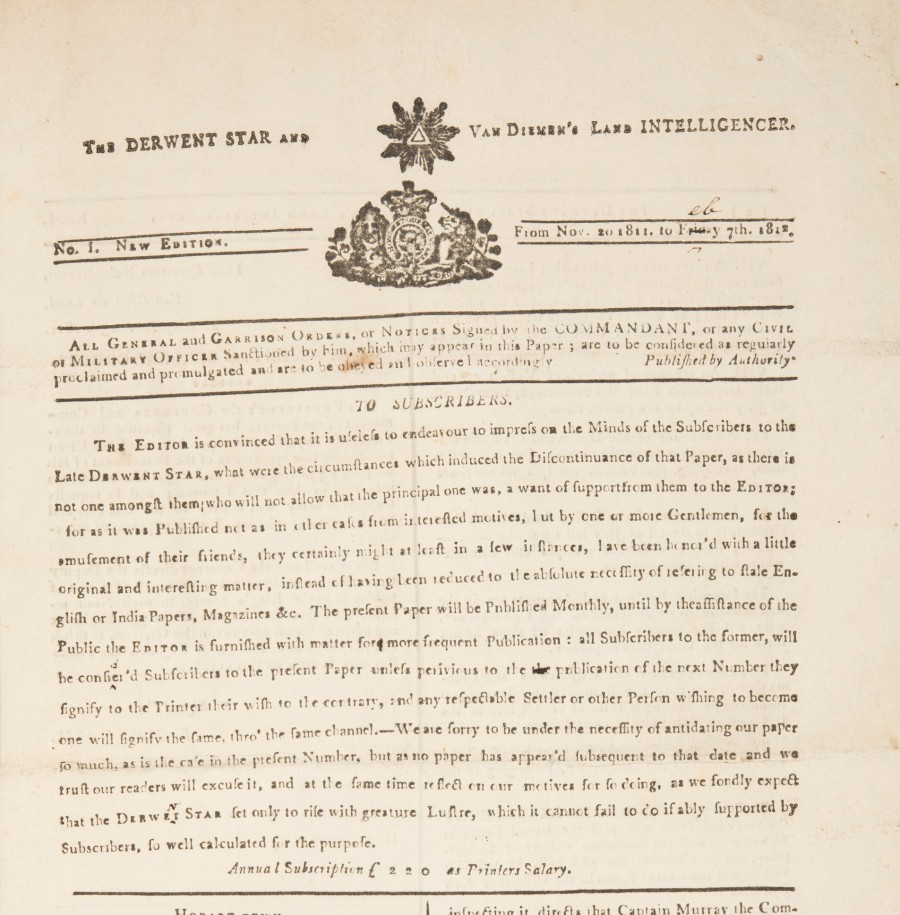

The same cannot be said for the only other surviving number, aptly described by Wilson as ‘a curious specimen’. This was published in February 1812 and was an attempt to revive the paper after a lapse. The only known copy, in the Mitchell Library, is printed on two leaves (four pages) of laid paper. It contains a description of Macquarie’s recent visit to Van Diemen’s Land and numerous government orders and notices issued during it, including Macquarie’s instructions for improving the layout of Hobart Town. The standard of the typography leaves much to be desired.

- Masthead: No. 1. New edition (from Nov. 20, 1811 to Friday [crossed out and Feb written in pen] 7th 1812.

- Imprint: Printed at the Government Pres [sic], Hobart-town by G. Clark, Printer, by whom all [advertisements – the type is very faint but it appears that some letters have been omitted] are recived [sic].

- Printer’s announcement: The Colonists lettrr [sic] and Tyro’s Poetic peice [sic], were from the number of General Orders unavoidable [sic] omitted, but shall appear in our next.

Despite hopes that the Derwent Star would ‘rise again with greature [sic] lustre’ as a monthly publication, this issue seems to have been the last. Perhaps an annual subscription of two guineas (for the printer’s salary) was too much to pay for a publication so riddled by printer’s errors.

View issues of the Derwent Star on Trove (note that no. 7 is scanned from the facsimile and not the original printing)

First Van Diemen’s Land book

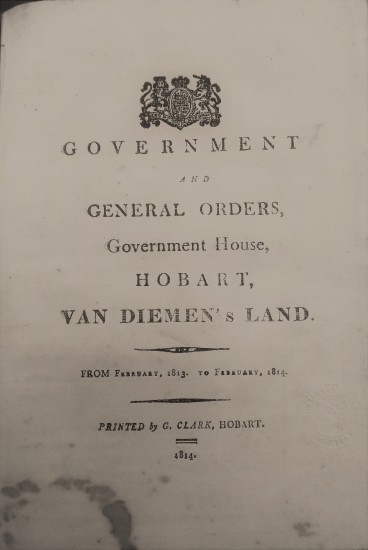

In February 1813 Thomas Davey arrived as the new Lieutenant Governor. About a year later Clark printed a 36-page compilation of orders and proclamations issued during his first year in office. The only known copy, in the Mitchell Library, is bound with other items in a volume inscribed by Davey’s son in law, James Scott. The last order included is dated February 1814, so it was probably printed around that time. Clark is not designated Government Printer so it is not clear whether this pamphlet was an official government publication or a private commercial venture. All the notices in it would have been originally printed by Clark.

Pages have been trimmed to 202 x 145 mm. The pagination, as in some of Bent’s early pamphlets, exhibits a curious reversal of the usual convention — beginning with the number [2] on the recto of the first leaf after the title page. The simple title page is attractively laid out but printer’s errors abound within. Some may have been in the original manuscript or due to unclear handwriting, but only the printer, perhaps having trouble with his eyesight, or his sobriety, could have been responsible for ‘Governmet House’, ‘quartly returns’, ‘conveienently’ and for dating one order 1831 instead of 1813!

Van Diemen’s Land Gazette

On 31 Jan 1814 Clark was granted a conditional pardon (sent to Davey on 12 March) and in May he commenced another newspaper. While still a convict he had been paid a salary for printing the Derwent Star. The new paper, while still printed at the government press, by a man now designated Government Printer, appeared to be, at least in part, his own commercial venture, similar in nature to the Sydney Gazette and Bent’s later Hobart Town Gazette. No record of Clark’s formal appointment as Government Printer has been found.

Unlike all the earlier surviving examples of Clark’s printing, where he is recorded as ‘G. Clark’ the Gazette, except for one misprint as ‘Clake’, consistently uses ‘Clarke’ in the imprint and advertisements alike. Advertisements indicate he had a sideline in printing and selling forms.

Several copies of the inaugural issue were sent to Sydney. On 4 June the Sydney Gazette of 4 June noted the commencement of the fortnightly paper, solicited subscriptions (two guineas annually) and made a few extracts. There are no surviving copies of this first issue. Issues 2 to 9 are held in the Mitchell Library and are available on Trove. The reasons for the paper’s cessation are unclear. Although it has been generally stated that no. 9 (10-24 September 1814) was the last issue, extracts in the Sydney Gazette early the following year indicate that there must have been at least one more in October.

In his 1829 almanack Bent rather dismissively described Clark’s Gazette as ‘containing about half a dozen advertisements, &c. and printed once a fortnight, on half a sheet of foolscap, by George Clark; but which, like the “Derwent Star”, ceased to be published in a few weeks after its commencement’. On a number of occasions Bent implied that no paper anything like his own had previously been published although a comparison of the Van Diemen’s Land Gazette with the early issues of the Hobart Town Gazette indicates this was not strictly true. Bent never ever referred to working as Clark’s assigned servant or being involved in the printing of Clark’s Gazette although given his experience in a London newspaper printing office he would have been well qualified to assist Clark with a newspaper. He probably contributed to the reasonable standard the Gazette managed to achieve under difficulties. Bent was always reluctant to broach the touchy subject of his own criminal background, and equally wary about his relationship with Clark and the circumstances under which, during the ill documented time of Davey’s administration, he succeeded him as Government Printer.

Clark and Bent

Bent arrived in Hobart on 19 February 1812, just a few days after the last number of the Derwent Star appeared. He was one of eighty convicts Macquarie, fresh from his recent tour of inspection, selected for their usefulness to the southern settlement. It was probably no accident that a printer was included along with other mechanics and artisans.

It is not clear exactly when Bent began working for Clark. He later told Bigge that he had been ‘printer in this colony’ since 1812, perhaps trying to give the misleading impression that he had been Government Printer since that year. Fawkner confirms that Bent succeeded Francis Barnes as Clark’s assistant. He also clearly describes the early relationship of Clark and Bent as that of ‘master and man’. Another remark about ‘Glenarchy’ being ‘cultivated by the hoe’ insinuates, rightly or wrongly, that immediately after arrival Bent may have been on the business end of such an implement.

Barnes was a man with diverse interests – barber, parish clerk and printer’s devil according to Fawkner. As early as 1808 he ran one of Hobart’s earliest pubs, the ‘Hope and Anchor’ and by 1813 he was free. He probably had better things to do than assist Clark.

It appears that Lieutenant Governor Davey sacked Clark sometime in 1815 and replaced him with Bent. Bent’s own statements are somewhat inconsistent, but his petition to the House of Commons (1836) states he was appointed Government Printer in 1815. This is borne out by the imprints of the few surviving newspapers and pamphlets from the period. There is absolutely nothing recorded officially about the event or the surrounding circumstances. Only a few senior appointments are noted in the Historical Records of Australia, which of course has huge gaps for the Davey period. It is worth noting that one of Macquarie’s despatches reveals his tetchiness about the number of appointments made by Davey without consultation.

One might expect to find something recorded in Davey’s Order Book (in the British Library and available on AJCP). This records a number of appointments at overseer or superintendent level and also Davey’s dismissal of the gaoler for ‘improper and disrespectful conduct’ but is silent on both Clark and Bent. In 1824 Lieutenant Governor Arthur was thwarted in his attempt to ferret out the nature of Bent’s appointment. He could find absolutely nothing on record in the office. His predecessor Sorell was unable to enlighten him as it all happened before his time. So we have to rely on second hand accounts, some from people with a bone to pick with Bent and not all of whom were present at the time. Reference to Bent’s early history with George Clark was always a sure-fire way of cutting him (Bent) down to size.

The general drift is that Bent was an interloper who took some sort of unfair advantage of Clark, or was favoured, perhaps somewhat capriciously, by Davey.

We know about Clark’s sacking from two sources — Andrew Magill, who was in Hobart at the time, and John Pascoe Fawkner, who was not, having been transported to Newcastle for three years in 1814. Magill, writing in 1825, said Bent was ‘taken from government labour’ and put into the position after Davey had sacked Clark. Fawkner said Clark was ‘given to drunkenness’, perhaps implying this had been the case before Bent was assigned to him. Bent, being a sober man, ‘soon worked Clark out.’ Fawkner also refers to some sort of disagreement and ‘a clever manoeuvre’.

Jorgen Jorgenson, writing to Arthur in 1836, with obvious intention to undermine Bent’s petition and curry favour for himself, implied that Clark did not pay close enough attention to his business and left the day to day running of it up to Bent. Bent, by starting up his own newspaper, had defrauded Clark of his property. There was ‘ill blood’ between the two men ever after. An alternative reading is that perhaps Clark sat back with the bottle and left Bent to do all the hard work.

In 1827 Robert Howe described how the right to print the Hobart Town Gazette was then in dispute between his half-brother, George Terry Howe and James Ross. They had been appointed joint Government Printers when Bent was sacked in 1825 and subsequently fell out. Howe’s view was that Bent should have paid Clark for the copyright of his paper (but did not) and that in a court of law neither the government, his brother nor Bent would stand a chance against ‘Clark the fisherman’ who was unaware of his legal entitlements but ‘ought to have a good round sum for his patriotism in founding such a journal.’ Sydney Gazette 13 Mar 1827

1815 was a fraught year for Van Diemen’s Land and for Davey. The bushranger situation had gotten completely out of hand. Macquarie, hardening in his view that Davey was unfit for office, was furious when Davey illegally declared martial law on 25 April. At that time the Hobart Town printing office would have come under intense pressure with proclamations and government orders urgently required. Clark’s shortcomings and unreliability may have become glaringly evident to Davey.

Late in August 1815 a whaling ship about to return to England presented Davey with an opportunity to send a despatch directly to the Colonial Office, behind Macquarie’s back. He was desperate to create a good impression and among the voluminous enclosures were items printed by Andrew Bent which would have assisted him to do just that – four neatly reprinted proclamations spanning 1813 to 1815, and a flattering address from the settlers telling Davey what a good fellow he was for declaring martial law. It is not clear whether Bent printed this at the Governor’s behest, or for the committee which drew it up. The chairman of the committee being Edward Lord, some sort of skulduggery was quite on the cards. Before year’s end Bent’s name appeared as Government Printer on the Port Regulations even though he was still a convict at the time and his conditional pardon was not granted until well into 1816. Perhaps the post of Government Printer and the early granting of his emancipation were rewards for services rendered. Bent received his conditional pardon after only four years of servitude while Clark, also a lifer, had to wait fifteen years for his.

Later life

In 1814 Clark had advertised a boat for sale. Perhaps he failed to find a buyer because after his sacking he earned his living out on the river. In September 1816 he advertised that, having just purchased ‘a capital fishing seine’, he could offer a regular supply of fish and oysters. In a deposition in 1817 he stated ‘I am a waterman and have a licence to ply a ferry boat to go to the shipping in this harbour’. From later accounts this was an old whale boat. In 1820 he received a payment from government for boat hire. He is listed in Bent’s early almanac directories as a Waterman in Collins Street, and that is the occupation recorded at his burial. Bent’s 1826 sheet almanack records him charging one shilling for each person (two shillings if the ship was already unmoored) and one shilling for each trunk, bag or box.In February 1825 R. L. Murray, writing as ‘A Colonist’ and agitating against the acting Naval Officer, effusively thanked Clark for his assistance in ferrying three gentlemen (obviously including Edward Lord and himself) out to the Denmark Hill.

Clark also had a brief career as a constable. He was appointed in August 1817. According to a notice in the Gazette he resigned in October 1819, although a victualling list in the Bigge Commission papers notes him as ‘struck off.’ In October 1817 he traveled to Sydney on the Pilot, having been summoned as a witness for what he describes as a court martial, but was probably the trial of several bushrangers who were sent up on the same vessel. Clark’s letter asking for reimbursement of expenses mentions he had a wife and family to support ‘at home’.

We will probably never know for sure whether Clark’s sacking was justified, or whether Bent, with an eye to the main chance honed during his early struggles to survive in London’s slums, took some sort of unfair advantage. It is understandable that Clark would later feel resentful at what had occurred. While he got cold and wet out on the river, his former assigned servant, a little whippersnapper nearly twenty years his junior, took over his job, commenced another newspaper on the ruins of his own, established himself, for a time at least, as a highly successful business man and eagerly accepted the cognomens ‘Father of the Tasmanian Press’ and ‘Tasmanian Franklin’. It is easy to imagine Clark’s ironic thoughts in 1825 when Bent, deprived of the Gazette title and sacked, in his turn, from the position of Government Printer, cried ‘Piracy!’

There is no evidence that Clark worked again as a printer. He appears to have got on with his life and as far as we know made no formal protest about his sacking. But resentment (and talk) lingered like a bad smell. Clark died in Hobart on 3 November 1831 and was buried two days later. An anti-Bent newspaper could not resist the opportunity to score a point.

DIED. On Thursday morning, at his house in Collins-street, aged 56, the real Franklin of Tasmania, Mr. GEORGE CLARK, who, with Mr. Francis Barnes, of Ralph’s Bay, were the first Printers in this Island, and who so continued for several years, until others were taken from very different work by the Government, to serve under them. (Tasmanian 5 Nov 1831)

Further reading: I. Wilson. Collecting Old Tasmanian Books, Melbourne: Boobook Press, 2010.

Many thanks again, Sally.

I am in awe of the detail you always seem to find – it does make such interesting reading.

LikeLike

Excellent story. I’m currently researching Andrew Bent for a tree I’m working on. Thank yu very much for your detailed account.

LikeLike