Of all the friendships Andrew Bent formed in Hobart Town his bond with James Austin, an original Calcutta convict, ran especially deep. Their relationship appears to have been one of mutual affection and respect. Towards the end of his life, Bent, addressing Austin’s two nephews, Solomon and Josiah Austin, referred to ‘the reciprocal friendship you so long witnessed between your late beloved uncle and myself’, describing Austin as ‘a man whose friendship was the only thing in human affairs that I valued in this world – a true friend who loved his friend nothing more [sic] than he did himself’. This was written after Bent had a major falling out with the nephews, and when his mental health was breaking down, but the depth of feeling for his old friend shines through. Bent was also good friends with Austin’s cousin and business partner John Earle, with Austin’s companion and housekeeper Hannah Garrett and, until their relationship fractured in 1838-9, with Solomon and Josiah. The nephews arrived in 1825, and were, according to Lieutenant Governor Arthur, very industrious, enterprising and well conducted young men. For many years Austin and Earle – and the nephews too – provided loyal support to Bent and his newspaper through troubled times. Andrew and Mary Bent named a son, born in 1830, James Austin Bent, and another, born two years later, John Earle Bent. Their daughter Hannah may well have been named after Hannah Garrett.

The early years

Austin and Earle were farm labourers from Baltonsborough in Somerset. They arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1804 with the settlement party led by Lieutenant Governor David Collins. They were in their mid-twenties and had been sentenced to seven years’ transportation for stealing bee hives and honey from their uncle. In Hobart Town Austin was cook and valet to surveyor George Prideaux Harris. He appears to have behaved well. Earle, as gardener to the Reverend Knopwood, got into a few scrapes – digging up potatoes from the garden in broad daylight, breaking into Knopwood’s closet, and purloining timber to make a bed and table for William Stocker.

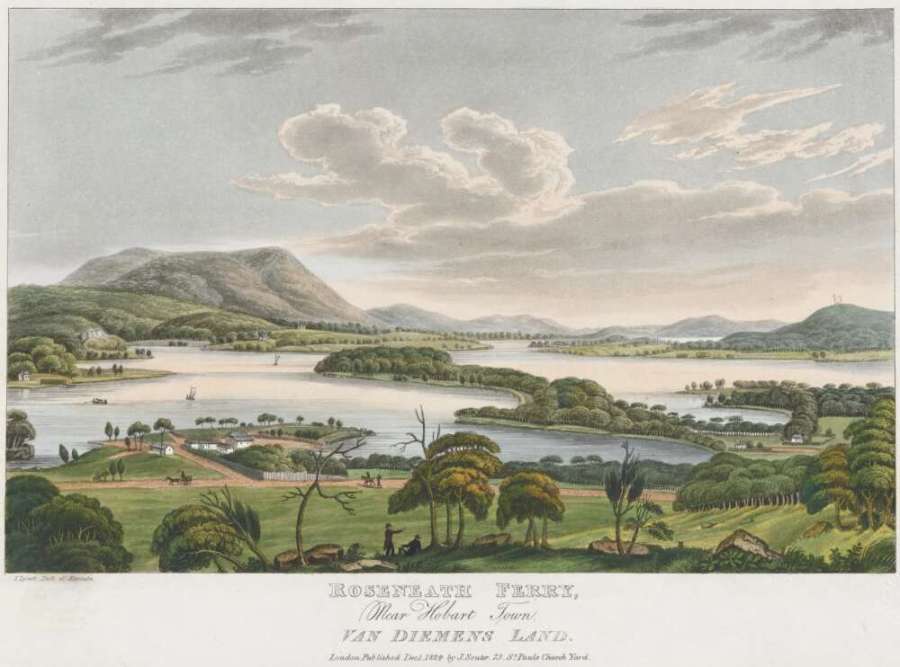

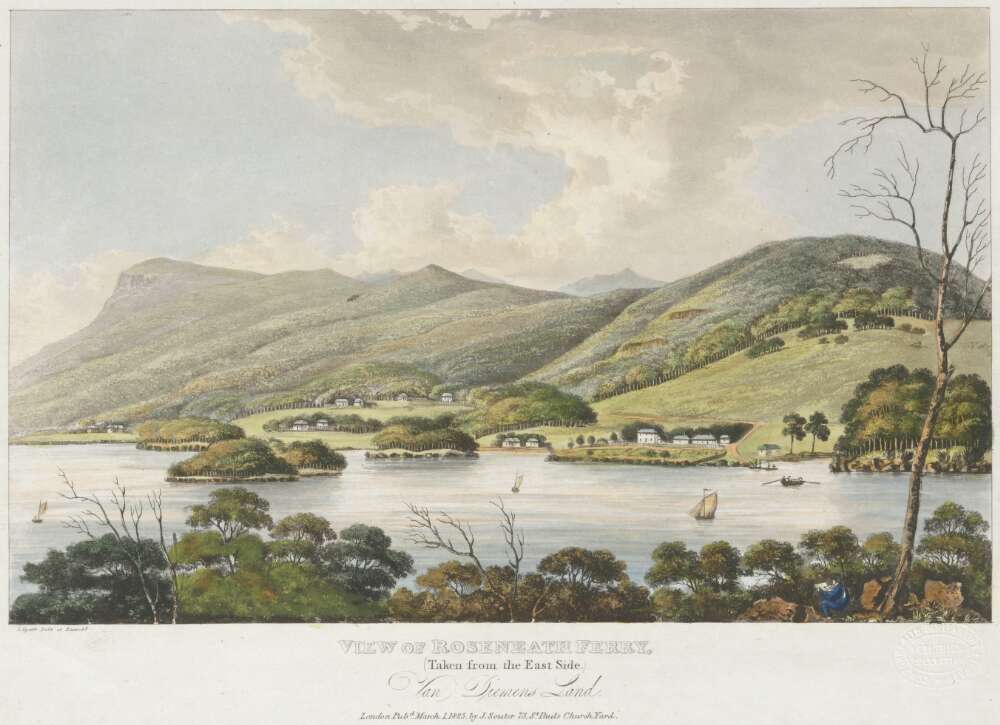

By around 1809 both Austin and Earle were free. Shortly afterwards Austin erected a small stone cottage by the water at what is now Austin’s Ferry. The building, which still stands, was probably there when Bent arrived in 1812. It was certainly in existence by 1814 when Knopwood sheltered in it during inclement weather. Austin named his Glenorchy property ‘Baltonsborough’, but in 1821, at Governor Macquarie’s instigation, it was renamed ‘Roseneath’.

The depth of the friendship between Bent and Austin suggests their bond was very likely forged in the early days. A couple of hints – one, from John Pascoe Fawkner, being that when Bent arrived in the colony ‘Glenarchy was cultivated by the hoe’ – suggest that immediately after arrival he may have spent some time in general farm labour before being assigned to the printer, George Clark. It is quite possible that he worked for the Fawkner family who arrived, like Austin, in 1804, and who had a farm at Glenorchy, not far from Austin’s, from around 1806. Bent had almost certainly known the Fawkners in London. Or perhaps he was assigned to Austin himself. Either way it is not too much of a stretch of the imagination to picture Bent and Austin in that little cottage, by the fire, chewing the fat in a mixture of broad Cockney and West Country burr.

A success story

Although illiterate, Austin was a shrewd man, who ultimately became very wealthy. According to Marjorie Tipping, at the time of his death Austin owned 1480 acres of land by grant, a similar amount by purchase and two two-storey stone houses which, with outbuildings, were worth £2,500. Solomon and Josiah Austin described their uncle as a very wealthy but eccentric man. He certainly puzzled Arthur, who never quite understood why he was for a long period strongly opposed to his administration, or why, when the nephews applied for a land grant relying on their uncle’s wealth as guarantee, he absolutely forbade them to divulge any information to the authorities – an act which Arthur described as an ‘absurd instance of vanity and folly’. By acceding to this rather odd request Solomon and Josiah missed out on a grant to which they were fully entitled, but they ultimately benefited from remaining on good terms with Uncle James.

In the early days Austin provided a model for Bent of how an enterprising and industrious man could make a successful new life after transportation. Both men can be viewed as ex-convicts making good – or, perhaps more accurately, being ‘on the make’ and securing a monopoly on an essential service.

Austin soon established himself as a farmer, and by 1819 was supplying large amounts of meat and wheat to the Commissariat. In 1818 a golden opportunity presented itself when he and Earle received a licence to run a ferry service across the Derwent River. This venture proved extremely lucrative, especially as they erected an inn on each side. In 1826, the Land Commissioners, after enduring a two-hour delay and much insolence from the boatmen while a cart became jammed (twice) between the punt and the jetty, wrote scathingly about this important service. They concluded it had become a mere money-making concern for its owners and ‘if steps be not taken to relieve the Colony from the exactions and delays of this ferry … everything like improvement must be given up.’

James Austin and the Colonial Times

A local Act passed in October 1827 required newspapers to be licenced at the governor’s pleasure. Bent’s newspaper was the chief reason the Act had been deemed necessary so when he applied for a licence he was, predictably enough, refused. Austin did his best to help his good old friend by agreeing to purchase the Colonial Times. Some sort of transaction obviously did take place. The consideration money – £600 pounds in bills drawn by Bent according to Jorgen Jorgenson – was, they said, handed over in the office of solicitor Gamaliel Butler, and the deed was witnessed by two of Butler’s clerks. Austin then wrote asking for a licence. He and Bent fronted up to the Colonial Secretary’s Office to swear that Austin was the sole proprietor, although Bent would still print and publish the newspaper. Jorgenson later asserted that a nervous Austin confided to him that the sale was only ‘under a colour’ and that the bills would be torn up once a licence was granted. Jorgenson warned Austin that he might lay himself open to a charge of perjury if the truth later came out, as it surely would.

Bent himself admitted that the contract included a provision for him to repurchase the newspaper for the same price at any subsequent time. It was thus patently obvious to both Arthur and his Executive Council that Austin’s application was really only a renewal of Bent’s under another name. Austin’s application was therefore refused. The council further concluded that even if the sale were genuine, Austin was not fit to run a newspaper as it was well known that he was illiterate. This had just been demonstrated when he and Bent made their affidavit and Austin had to make his mark rather than signing. It is therefore curious that a number of letters in the long chain of correspondence relating to the licence for Bent’s newspaper (in TAHO CSO1/1/207/4925) were ‘signed’ by this illiterate man – and in several different hands to boot!

This attempt at deception did not enhance the credibility of the pair although whether Austin himself was aware of it is unknown. Most of the letters were, apparently, dictated by another of the printer’s good mates, Bartholomew Broughton.

The Newspaper Licence Act was repealed at the end of 1828 and so, at the beginning of 1829, after a period when the Colonial Times had been reduced to a gratis advertising sheet, it returned to being a full newspaper. Other provisions from 1827 remained. One of these required printers and publishers to give bonds or recognizances which would be forfeited after any conviction for seditious or blasphemous libel. When Bent betook himself to Chief Justice Pedder’s white stuccoed house in Macquarie Street on 9 March 1829 to make his recognizance he was accompanied by his two loyal friends, James Austin and John Earle, who put £200 each on the line as the two guarantors required by the Act.

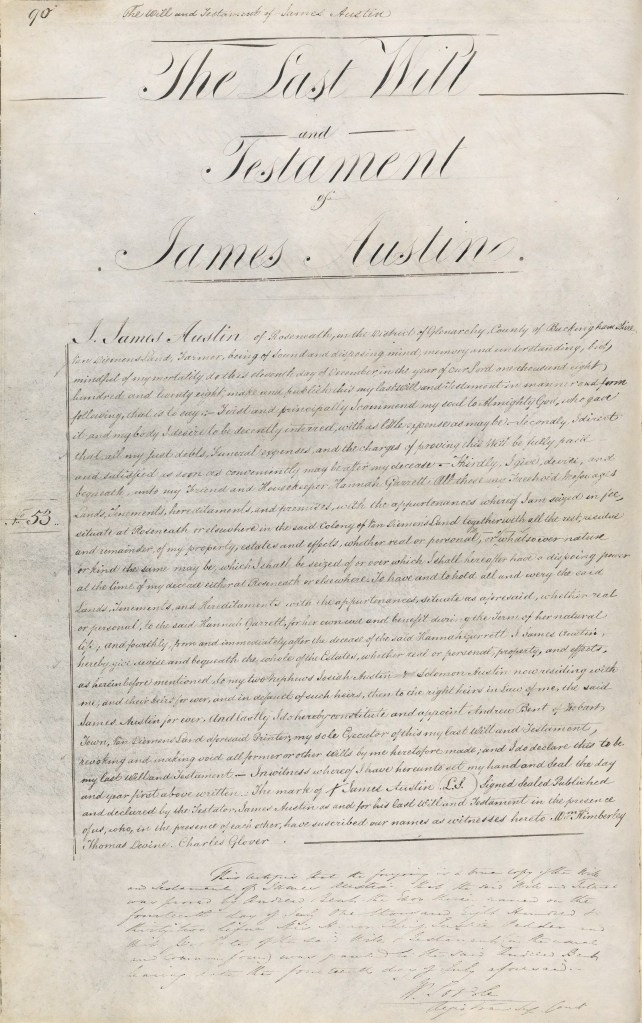

James Austin’s will

In September 1828 James Austin narrowly escaped drowning when his favourite black horse was swept away from under him while he was attempting to cross a flooded creek. Austin, at 52, was getting on in years, and this reminder of the uncertainty of human life may have prompted him to make his will. On 11 December he sat down to compose it with his good friend Andrew Bent by his side. He appointed Bent his sole executor.

If Bent’s own later recollections are to be believed, Austin wished to leave legacies to Bent’s children, but Bent refused to accept this generous gesture, and later came to regret his decision. There is no independent evidence to support his assertion, but it it quite credible. Austin had no children of his own. It is easy to see how he and his friend Hannah Garrett may have been fond substitute grandparents for Bent’s little ones, who when lined up would have presented a picture of steps and stairs.

Hannah had arrived free with her purported husband, Richard Garrett, a convict on the Calcutta. When Lieutenant Governor David Collins discovered they were not in fact married he insisted they tie the knot, and theirs was the first marriage in the Calcutta contingent, taking place while they were all still at Sorrento. After her husband’s death Hannah lived in the town until around 1827 when she moved out to ‘Roseneath’ to keep house for Austin. Andrew Bent junior, in his old age, remembering some of the old identities of Hobart Town, specifically mentioned Hannah Garrett.

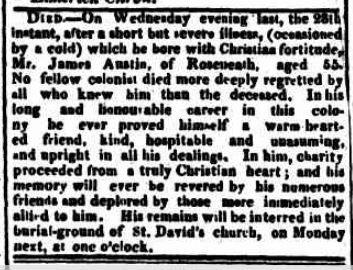

James Austin died at ‘Roseneath’ on 28 December 1831. He was buried in St. David’s cemetery, the funeral leaving from Bent’s dwelling in Elizabeth Street. The general high esteem in which he was held is reflected in this obituary, which reads as though it could have been written by Bent himself (although it almost certainly wasn’t)

Bent was granted probate on 14 June 1832, but the administration of his old friend’s estate proved to be far from straightforward. Perhaps he was a bit lax, because he did not at that stage advertise for creditors and debtors to come forward, although it seems a substantial debt owed by Edward Lord was paid.

Austin left everything to Hannah Garrett, until her death, when the two nephews were to inherit. Solomon and Josiah leased their uncle’s property from Hannah for £350 a year. It was not long before the parties were in dispute as Hannah fell victim to a wily fortune-hunter.

Enter George Madden

On 29 March 1833 Hannah advertised that she had appointed John James Holland, a clerk in the Police Office, (the significance of this will soon emerge) as her agent. This prompted Bent to advertise the following week, calling in any debts to the estate, to be paid to him, as executor, or to Solomon and Josiah. The nephews, perhaps getting a little ahead of themselves, also advertised their reversionary interest in the estate, pointing out, rather unkindly, that Hannah was nearly seventy. Hannah claimed the nephews had been selling off some of the stock and Holland advised he was about to file a bill in equity in the Supreme Court, to obtain a full disclosure of the extent of James Austin’s property, which had never been made, asserting also that Hannah did not understand the nature of the lease which she had signed. Bent countered that the insinuation that the lease had been surreptitiously obtained conveyed an imputation on the Messrs. Austin and was completely groundless. He was present himself, together with John Earle and a Mr. T. King, when the lease was carefully read over and explained to Hannah, and Mr. Earle, in particular, minutely examined and compared the lease and its counterpart on her behalf.

The purpose behind all this manoeuvring soon became clear. On 3 May Hannah married convict constable George Madden. No ages are recorded in the register, but the newspaper announcement, probably exaggerating in both directions, described the groom as 32 and the blushing bride as 73! A few days before the ceremony, in preparation for the marriage settlement, a formal deed transferred Hannah’s property into the hands of trustees – her agent Holland and John Ogle Gage.

Madden had arrived only the previous year, transported for robbing the Doncaster betting room of £1,700 in notes and gold. Notwithstanding this serious offence, he was immediately made a constable and stationed at ‘Roseneath’. According to newspaperman Gilbert Robertson he was a prime example of the disgraceful favouritism shown to some convicts, and he soon became a favourite of Chief Police Magistrate Matthew Forster. By marrying Hannah, Robertson asserted, Madden obtained possession of an elegant residence and enough money to live in the style of an English squire, thus (the corrupt system being as it was) placing himself above all convict discipline. It was equally disgraceful that the governor had sanctioned the marriage.

In 1834 Hannah’s trustees conveyed the property outright to Solomon and Josiah in exchange for an annuity for her. But bad blood remained. The following year Madden appeared in court charged with giving Solomon a violent cut across the face with a whip when his cart and Solomon’s stagecoach jostled for room when passing each other on the New Norfolk road. Madden was found guilty but, rather than being sent to a road party as might have been expected, was only fined £2 and costs. Solomon, on the other hand, was taunted by his friends that a convict could horsewhip him at any time for 40 shillings.

Hannah lived until 1841 but her wedded bliss may not have lasted long. Gilbert Robertson, in his always colourful but only sometimes truthful style, alleged that Madden soon began an amour with the estranged wife of Ikey Solomon.

A falling out

After Austin’s death Bent’s friendship with John Earle and with Solomon and Josiah continued. In 1835 some of Bent’s cattle were running on John Earle’s property at the Eastern Marshes. When Bent commenced his own newspaper again with Bent’s News at the beginning of 1836, John Earle and Josiah Austin were his guarantors, and when fresh recognizances were made the following year, Earle and Solomon Austin fulfilled that role.

During this period Bent’s financial situation deteriorated badly. In 1838 he wrote to the Colonial Secretary asking for free passage to Sydney on one of the convict transports. He admitted to being £1500 in debt, but investigation has shown this was a serious understatement. His friends Solomon and Josiah had obviously helped him out with loans, and he was also indebted to others. The crunch for the Austins came around August 1838, perhaps because Bent had again asked them to provide sureties for his paper (these had just been increased by a new law). Bent had recently been convicted of several libels, and although let off the damages for one, and, it was believed, indemnified by the author for another, his legal fees would have been crippling. Solomon and Josiah were apparently prepared to extend their credit, but not unreasonably wanted to have some security over Bent’s property. They waited on Bent several times in company with their solicitor Gamaliel Butler (whose presence might not have helped matters as in 1830 Bent had to pay him £80 damages for libels published in the Colonial Times), but Bent repeatedly refused to co-operate. The reasons for this remain unclear although Gilbert Robertson put it down to stupid obstinacy and pig-headedness.

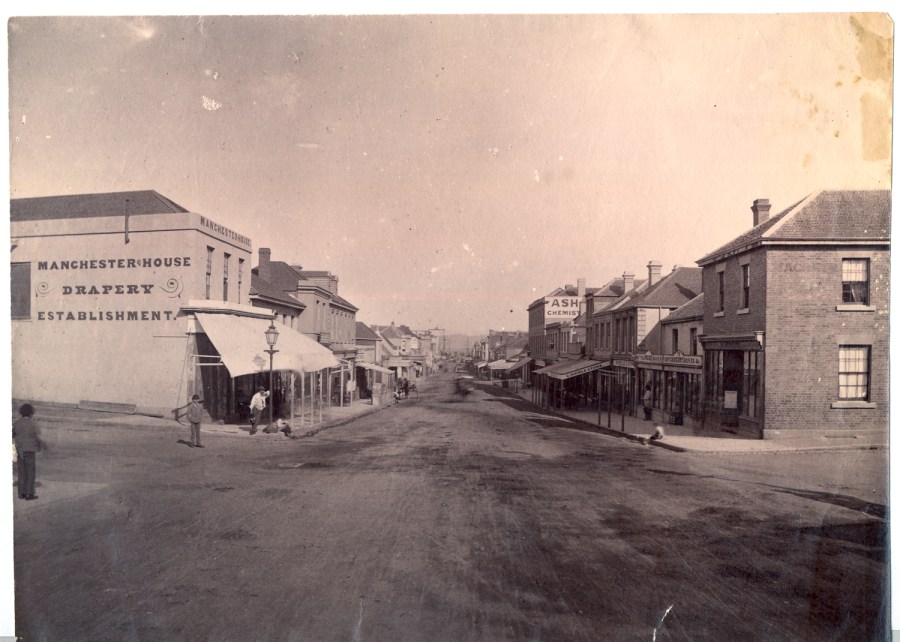

This left Josiah and Solomon little option but to take matters to court. They were not the only ones. They sued him for £1,100 and Stephen Adey (of the Derwent Bank) did the same for the amount of £950. In January 1839 Bent’s Elizabeth Street property, consisting of the two story brick printing office, his two story stone dwelling house and shop, a butcher’s shop, and a livery stable out the back, together with a job lot of furniture and other goods and chattels, was sold by the Sheriff. Bent was bitterly disappointed with the result. His property – ‘the Temple Bar of Hobart Town’ – fetched just £1700. He had not all that long before refused an offer of £5,000 for it, or so he said. The photograph below shows Bent’s stone building later in the century when it had become ‘Manchester House’.

To add insult to injury Bent’s property was purchased by the Austin brothers themselves. It is possible that they were only bidding to try to help their old friend out, but in later years an impoverished, bitter and increasingly irrational Bent lashed out at them in the newspapers, accusing them of deliberately forcing the sale so they could buy up the valuable property at their own price and of selling it soon afterwards for a handsome profit. It is true that they sold to R. S. Waterhouse within six months for £300 more than they paid, but Bent’s attacks appear to have been libelous and largely unfounded. At the time of writing in 1849 he was labouring under some truly bizarre delusions about what his role as Austin’s executor entitled him to do.

Epilogue

John Earle, who married but later separated from his wife, died in 1840. He was buried at St. Davids in the same grave as his cousin.

Sadly, there is no evidence that the rift between Bent and James Austin’s nephews ever healed.

Solomon and Josiah became wealthy men on the back of their pioneering uncle’s earlier success. Neither of them ever married. After they died James Austin’s property passed to other family, some of whom had come to Tasmania from Somerset in 1831, arriving, unfortunately, just after his death. Not all stayed, but two other nephews, James and Thomas Austin, brothers to Solomon and Josiah, did, and enjoyed great success in Tasmania and more especially in Victoria. They played a prominent part in the breeding of stud merino sheep. Both became well established in the Geelong district. Thomas erected a mansion at ‘Barwon Park’ and his wife Elizabeth founded the Austin Hospital.

Three of Andrew Bent’s sons (Andrew Bent junior, James Austin Bent and Francis Augustine Bent) also moved to Geelong. It is not known whether they had much, or indeed any, contact with the Austins – they would have moved in rather different social circles one would think – but it is rather poignant that in the Geelong Eastern Cemetery the modest grave of Andrew Bent junior and family is next to the impressive tomb of Thomas and Elizabeth Austin.

Further reading: Marjorie Tipping, Convicts unbound: the story of the Calcutta convicts and their settlement in Australia, Ringwood: Viking O’Neill, 1988

Thank you Sally.

Another fascinating account of the life and times of Andrew Bent!

Was not the Geelong Austin the gentleman credited ( though debited would be more appropriate) with introducing the rabbit to Victoria?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Thomas Austin is generally regarded as the culprit, although he may not have been the only one. In 1859 he released 12 pairs of wild rabbits at Barwon Park, to provide sport. Just a few year later Prince Alfred, visiting, apparently shot over 400 in 3 1/2 hours. See https://australianfoodtimeline.com.au/wild-rabbits/

LikeLike

These well to do Austins loomed large in my husband’s family who apparently liked to think they were connected to them. My husband’s father was named Austin after George Austin his mother’ mother’ father. George Austin however had no connection to the Barwon Park Austins but was an English born butcher who married Mary Amott the daughter of the convict compositor Thomas Amott about whom we have previously corresponded and who turned himself into the ‘Wizard of the South’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sally,

While, yes, others brought rabbits to Australia – the first fleet, Knopwood, for example – there is no doubt that Thomas’ rabbits were the ones that have spread throughout our country. Thomas and James’ nephew, Joseph Mack who married their sister, Annie, later wrote a Letter to the Editor explaining his role in transporting the rabbits to Barwon Park.

Cheers

Owen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Own, for providing that additional information

LikeLike

Thank you for a good read sally … I didnt know that the cottage was still standing and shall inspect it at my earliest convenience…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Once again, a fascinating read about the life and times of Andrew Bent, and, as always, meticulously researched. Thank you, Eve A

>

LikeLike