During the latter part of his life Andrew Bent’s mental health deteriorated badly, a process which may well have begun before he left Hobart early in 1839. Letters he wrote to the newspapers during his last few years in Sydney and the prospectus for a new business venture – a matrimonial agency of all things – show he had become quite delusional and irrational. His last decade (or more) was marked by increasing irritability and poor judgment.

Whether he suffered from some sort of age related dementia or from a psychotic condition is unclear. His difficulties may have been due to an inherited condition or caused by a stressful life during which he (rightly or wrongly) felt he had been persecuted and ruined by Governor Arthur. It is, however, impossible to avoid speculating that there may have been another contributing factor – an environmental one.

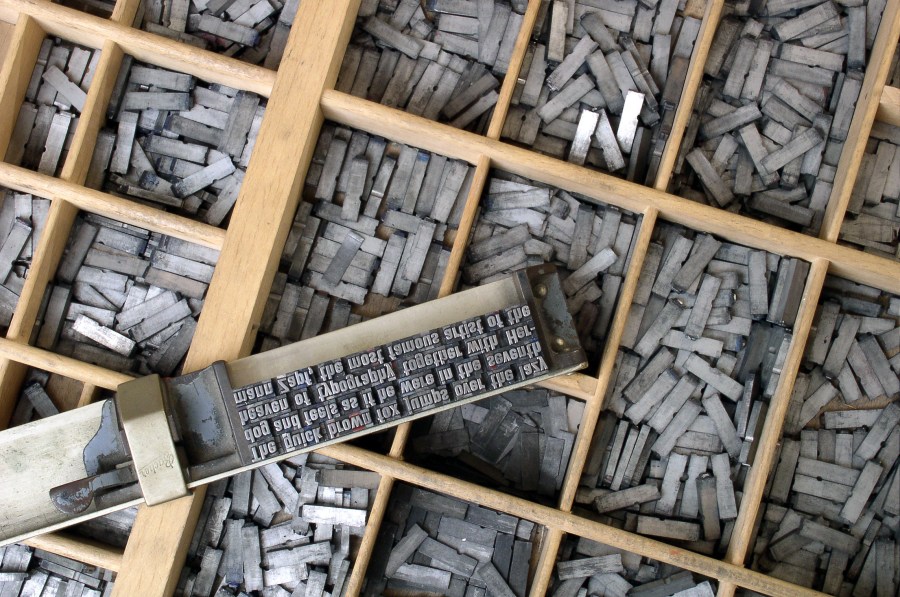

A recent article by Mila Daskalova, ‘Printing as Poison, Printing as Cure: Work and Health in the Nineteenth-Century Printing Office and Asylum, (Book History, Spring 2021) portrays printing as a generally unhealthy occupation. Common afflictions included tuberculosis, loss of eyesight, and the effects of intemperance. Another hazard was the insidious effect of chronic exposure to the lead in printing type. An article from 1890 quoted by this author mentioned printers as one of the four occupational groups that suffered most from lead poisoning. During his long career as a printer, indeed from his childhood, Andrew Bent would have been constantly exposed to lead type. Some compositors, it was said, even adopted the efficient but dangerous habit of holding type in their teeth, like dressmakers’ pins. So, while retrospective diagnosis can be a risky exercise, we cannot discount the possibility that he suffered from chronic lead poisoning. This can affect many parts of the body, including the nervous system.

Andrew and Mary Bent had eleven surviving children, all of whom would have been likewise exposed as youngsters. The fact that four of these children experienced significant mental health problems in adulthood would seem to be more than coincidence. Without speculating further on possible causes, this post takes a brief look at the stories of Hannah, Richard, Robert and Mary Bent (Steele) and the shadow cast over their lives by mental illness.

Hannah Bent (1828-1892)

In 1862 Andrew Bent junior advertised for the whereabouts of his siblings Robert, Richard, James, Edmond, John and Hannah Bent, obviously not knowing where any of them were. He eventually did discover Hannah’s fate, but it is not clear when or how. Her story is a particularly sad one. It is not known exactly when her mental illness began – although her father’s reference to ‘the serious affliction of one of my daughters’ (Colonial Times, 28 July 1848) may give a clue. What we do know is that from 1855 Hannah lived out her entire life in various asylums until her death in Newcastle in 1892.

Hannah was the Bent’s fourth and youngest daughter. She was born in Hobart on 5 or 6 May 1828. Nothing is known of her early life, although the 1841 census indicates she was then with her family in Kempsey. She appears to have returned to Sydney with her older sister Catherine and family in September 1845.

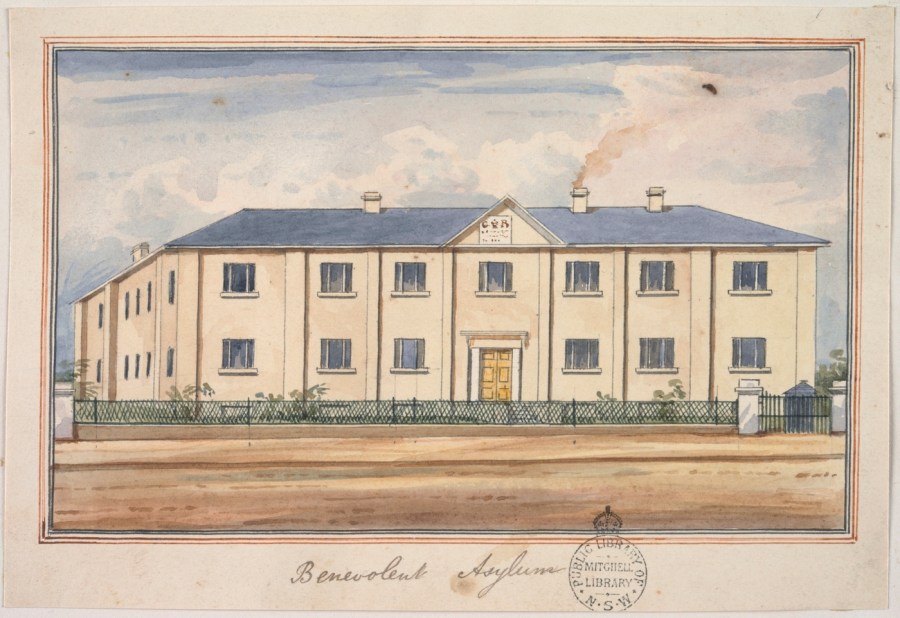

Perhaps, after Bent’s death in 1851, Hannah was cared for by Catherine. Whether or not this was so, Hannah’s troubles began in earnest soon after the Halls moved to Hobart in June 1855. Just four months after they left she appeared in court in Sydney, charged with being of unsound mind and unable to take care of herself. She was required to find recognizances for good behaviour or be imprisoned for a month. The first option being out of the question, she spent a short time in Darlinghurst gaol, where the records describe her as a slightly built woman, 28 years of age, 5 feet 5 inches (164 cm) tall, Roman Catholic, and (rather surprisingly) unable to read or write. On 6 December she was admitted temporarily to the Sydney Benevolent Asylum where her father had died just four years previously. It was while there she was certified as insane – on 22 December.

A week later she was sent to the Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum as a public patient, suffering from ‘mania and delusions’. The committing doctors opined that she would benefit from treatment there, but she had no means to pay for it, and no friends or relatives who could reasonably be expected to maintain her. In November 1856 she was transferred, with other chronic patients, to Parramatta Asylum, where she remained for over twenty years. On 25 November 1879 she was moved to the Newcastle Asylum.

The Newcastle institution had opened in 1871 in premises formerly used as a military barracks and industrial school. It served the dual purpose of an insane asylum and a facility to house ‘imbeciles and idiots’. It offered a somewhat more innovative and enlightened model of care than the older asylums. There were landscaped gardens and entertainment including cricket matches and concerts was organised for the inmates. Numerous patients were transferred from the overcrowded older institutions around Sydney. It is possible, though, that brother Andrew may have organised Hannah’s transfer, having finally discovered where she was, as he is recorded in the admissions register as her ‘friend’ or contact person.

Notes from Newcastle state that when Hannah was originally admitted to Tarban Creek in 1855 she was suffering from dementia, but was good tempered, harmless, and in good health. When received at Newcastle some 24 years later she was still suffering from dementia, now chronic, but remained in good bodily health, being ‘cleanly in her habits and giving but little trouble.’ She was ‘accustomed to associate words’. Hannah’s condition remained unchanged and her records are completely uninformative until June 1890 when, although only 62, she was described as ‘an aged woman, feeble, blind … and without interest or concern in her surroundings.’ On July 3 1892, after a day or two when she was observed to be ailing, but not seriously, she was found at about one o’clock in the morning collapsed and bleeding profusely from the mouth. She died shortly afterwards. A post mortem was conducted, the death certificate giving the cause of her death as a ruptured artery and haematemesis.

Hannah was buried in the Sandgate cemetery (Church of England section 24, lot 68) on 4 July 1892. Her grave is unmarked but the satellite image above shows its approximate location

Robert Bent (1826-?)

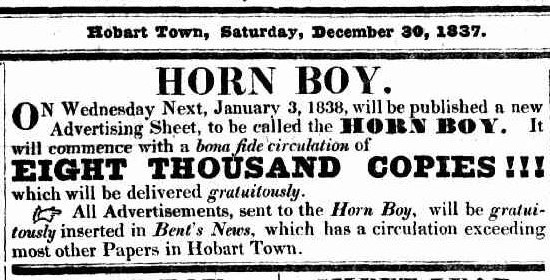

Robert was Andrew and Mary’s second son, born in Hobart early in 1826. By the latter part of 1837 he was, with his older brother Andrew, being trained as a printer by his father, delivering some of the deposit copies of Bent’s News and, in 1838, producing, with Andrew junior and the assistance of their older sisters, its short-lived supplement, the Horn Boy.

After moving to Sydney in 1839 the two boys assisted their father in his printing office in Pitt Street. In 1840 Robert moved back to Hobart, where he was employed at the Colonial Times. He was still there during the period of his father’s appeal for charity, being named in advertisements from 1844 to 1846 as one of the people who would receive donations in Hobart.

In 1842, in a letter to Governor George Gipps, Bent wrote proudly of his family. Robert appeared to be the apple of his father’s eye.

In Van Diemen’s Land; I have one son, a bright youth, and clever compositor; having at the age of 14 years, when employed on the Australian [sic] Chronicle, received a salary of upwards of £100 per annum; which the very talented and worthy Editor, Mr. Duncan, was often pleased to say he well earned, and deserved as much as any person on the Establishment; and though I now say it myself, I must cheerfully (and no one will perhaps dispute my competency to) confirm that gentlemans opinion; for a more skilful, dexterous, ready, and (if I may be allowed to use a Mechanical phrase) clean little “Typo”, no printing office could produce, or boast of, at his age, than the said Robert Bent himself.

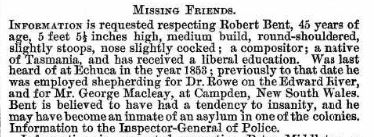

Robert possibly returned to Sydney late in 1846 during his mother’s final illness. Seven years later he was known to be in the Echuca district, having apparently abandoned his career as a compositor to work as a shepherd on various rural properties. When his brother Andrew advertised for Hannah in 1862, he obviously did not know where Robert was either. Andrew advertised again (for Robert and Richard) in 1871.

In 1872 the following notice appeared in a number of Police Gazettes.

Whether Andrew junior ever learned anything further is unknown. I have been unable to trace Robert after these notices appeared and have found no convincing death record anywhere in the Australian colonies or in New Zealand.

Richard Bent(1834-1913)

Richard was born in October 1834, the ninth of the eleven surviving Bent children. He was only six when the family moved to the frontier settlement at Kempsey so missed out on the liberal education his older siblings had received. Richard’s life was unconventional to say the least. He spent a great deal of his later life alternating between the gaols in Braidwood and Bombala, New South Wales, with over forty admissions altogether.

Richard may not have been quite as stupid or mad as some people thought, although there is no doubt he was eccentric, and had a taste for sleeping rough in the bush. He lived, as one newspaper put it, ‘on the fat of the land – poultry of all kinds, and vegetables of every description – obtained by blackmail levied upon any party’s property on which he felt inclined to locate.’ He received occasional convictions for petty theft, but most of his convictions between 1865, when he turned up at Araluen, and the early 1880s were for vagrancy. He was variously described as idle and disorderly or being an incorrigible rogue and vagabond. He did not seem to have a major problem with drink, but he was no sooner released from Braidwood gaol after serving six months’ hard labour for vagrancy than he was convicted for another six-month stint in Bombala on a similar charge.

Unfortunately, despite these repeated gaol admissions, there is no photograph in Richard’s criminal records. The descriptions in the entry books are of a man 5 feet 9 inches (178.5 cm) tall, of medium build (becoming stout in the later years), with a fresh complexion, brown hair and brown or hazel eyes. He had 3 moles on his back, a scar on his left shin, and vaccination marks on both arms. Described in another newspaper as a ‘prowling pilfering vagabond’, Richard did seem to be unfairly targeted by the Braidwood police. His case was even raised in the NSW parliament on 18 February 1876, probably precipitated by newspaper reports from the previous June.

After further search the real culprit was arrested. Shortly after this Richard was sent, via Goulburn gaol, to Darlinghurst for examination to determine whether he was sane. He was examined on 13 July, but was sent straight back again. An earlier examination, in Melbourne in 1856, appears to have been equally inconclusive.

We get a bit more information about Richard from a Mr. J H Taylor of Braidwood who wrote to historian TD Mutch in the 1940s, after the latter had advertised in the local press for information about Braidwood’s ‘Dick’ Bent, wondering if he could have been Andrew Bent’s son. Taylor was a relative of Edmond Bent’s wife Lucy Taylor and knew Richard well. He recounted how Richard went to the Victorian goldfields as a very young man, made a small fortune, but then lost it through speculation in railway shares, and a shipwreck in which a number of horses he was sending to New Zealand were lost. These losses, according to Mr. Taylor, made Richard ‘demented’.

Mr. Taylor also described how the famous comedian, Horace Bent (Richard’s nephew), offered to help him and even to take him to live with him, but Richard declined, preferring his life the way it was. Things probably became a bit easier for Richard with the introduction of the old age pension. In his final years he lived with the Sullivan family doing odd jobs about the farm. Despite his history of rough living he remained in good health up until his death (in 1913) at the ripe old age of nearly 80. The local newspaper, reporting his death, blithely described him as the brother of the Victorian premier – wrongly named as Sir Robert Bent – but whether this nonsense originated from Richard himself or a careless reporter is unclear. Richard was buried in the Anglican section of the Braidwood cemetery.

Mary Bent(1822-1879)

Mary was the Bents’ third daughter, born on 2 July 1822. She was a bright girl, who, as a pupil at T H Braim’s grammar school in Hobart, won a prize in 1837. Her proud father reported it in Bent’s News. She was sixteen when she removed with her family to Sydney on board the convict transport Gilmore, which had just landed its cargo of malefactors in Hobart. It was probably during that voyage early in 1839 that she met her future husband, John Charles Steele, who was one of the officers on board.

John Steele was born in Bencoolen, Sumatra, around 1815. His father, the young British resident at Manna, died when John was about two. His mother died when he was twelve. John’s paternal grandfather, Charles Steele, was a London merchant and young John was sent to sea, gaining his experience on board East India Company vessels. He remained in New South Wales when the Gilmore departed Australian waters in 1840. By August 1841, when he married Mary Bent at Kempsey (where the Bents had been for eight or nine months already) he had become, for the time being at least, a settler on the Clybucca.

Early in 1843, while still residing at Kempsey, Mary Steele was subjected to a violent assault, ‘with intent’ by a decrepit old fellow known as Charley the Boatswain.

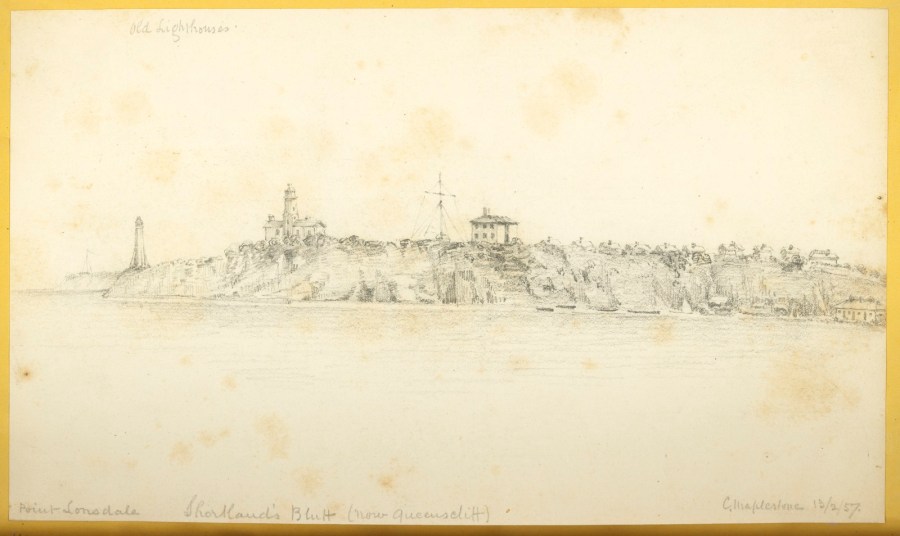

John and Mary later moved to Melbourne. Their first child, Charles, was baptised there in 1847. They had three more children – John, Mary Harriet, and Maria Francis (Fanny) who was born in Queenscliff in 1854. John had became a Port Philip pilot, probably sometime in 1852.

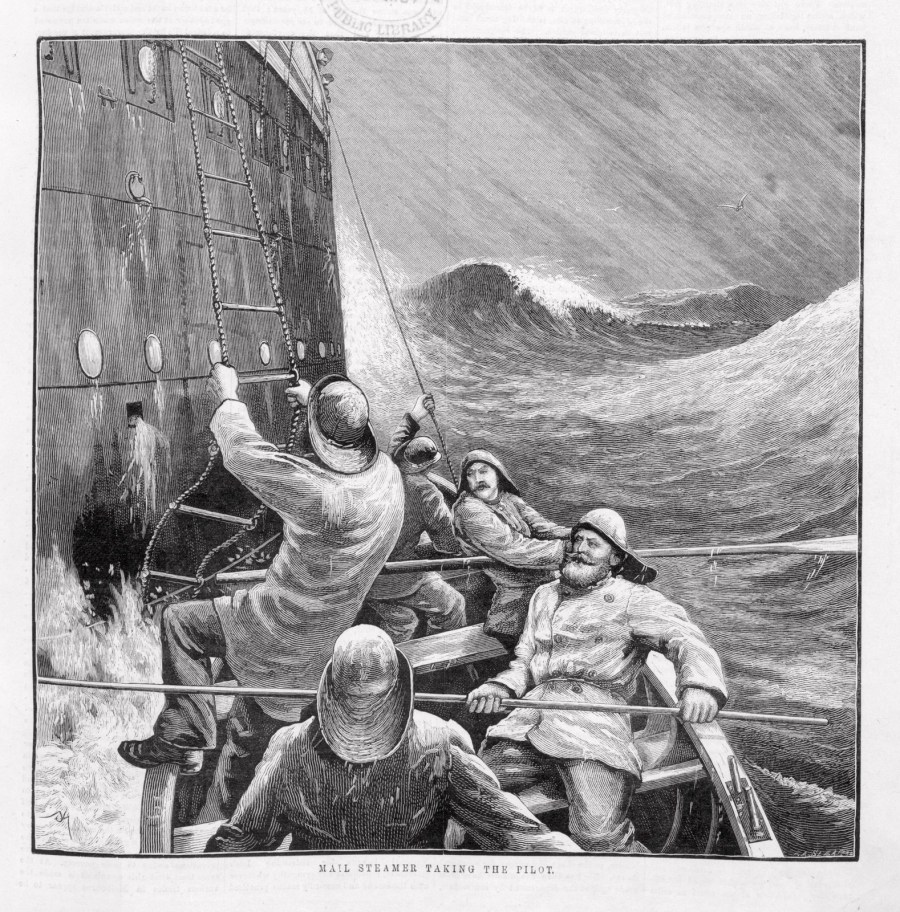

A pilot’s work was arduous, highly skilled, and not without its dangers. It involved going out to meet the ship in the pilot cutter, transferring to the ship in an open boat, then being responsible for navigating the tricky passage through the heads. Remuneration depended on how many jobs your team was able to obtain, and the size of the vessels. John’s team on the Proserpine was one of the most successful, but the Pilot Board reports show that, for reasons which are unclear, John Steele did no work at all for a six month period in 1855.

By this time the Steeles had moved to Queenscliff, where nine conjoined weatherboard cottages for the pilots were completed around the middle of 1854.

John Steele died suddenly at Queenscliff on 27 June 1856, from ‘apoplexy’. It is not clear whether Mary had mental health problems before John’s death. John’s not working for six months and a long delay in registering the birth of Fanny perhaps suggest all was not well. Postnatal depression is a possibility. Be that as it may, Mary certainly had a major breakdown soon afterwards. On 30 July, just a month after her husband’s death and three days after receiving a payment of £20 from the Pilot Board, she was examined by two doctors. Interestingly the application had not been made by Mary’s family but by Charles Ferguson, Chief Harbour Master and chairman of the Pilot Board, who was obviously concerned about her mental state. She was certified as being of unsound mind, and admitted, as a pauper patient, to the Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum three days later.

On 18 August the four children (ranging in age from ten years to eighteen months) were taken into the Melbourne orphanage. John Steele had died intestate, and administration of his estate was granted to one of his creditors. It was noted that the children were infants, the mother a lunatic, and it was not known whether there were any other relatives. The children were discharged from the orphanage in stages – the boys in 1857 and 1861; Mary Harriet in 1867; Fanny not until 1869.

The Yarra Bend registers list Mary as discharged into the care of friends, cured, on 14 Jan 1859, but the necessary warrant signed by two medical practitioners may not have been completed. She stayed on at the Asylum, working in the laundry. During this time she had what was probably only a single sexual encounter with a man named Sloane, who was an employee – night watchman and coachman to the Surgeon Superintendent. While no physical violence was involved, the encounter was unlikely to have been fully consensual on Mary’s part. Sloane appeared to have felt entitled to a return favour for having brought Mary some sewing materials from town. As a result Mary had another child, Sarah Jane Steele, who was born in Madeline Street, Carlton on 19 June 1860. Mary had left Yarra Bend when she realised she was pregnant and had taken refuge with her younger brother Francis. Sloane paid some maintenance for the baby, but when Mary asked for a larger amount, he offered instead, that he and his wife would look after the child. On 21 January 1861, about two months after she was taken into their care, little Sarah Jane died, aged eight months. The death was registered by Jane Sloane, and Sarah Jane was buried at Geelong.

Abuses at Yarra Bend

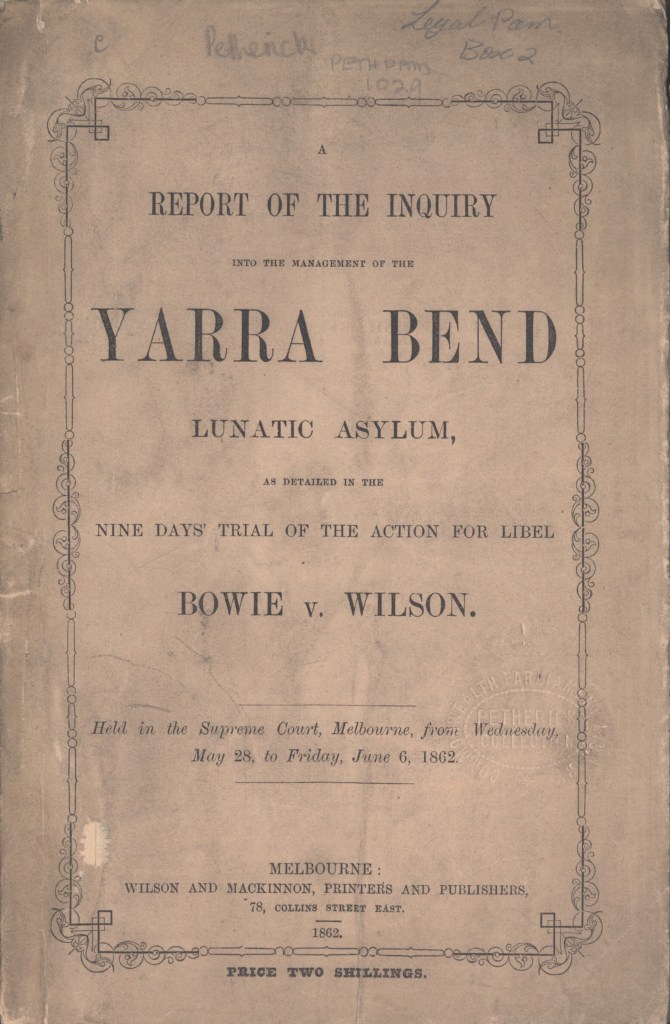

The Yarra Bend asylum had been established in the late 1840s, in a secluded and peaceful setting by the river. It was originally designed to house about 60 patients, but there had been an explosion in mental illness during the gold rush and by the time Mary was there the facility was dreadfully overcrowded. By 1858 there were 451 patients crammed into its forbidding prison-like greystone buildings. A Parliamentary enquiry in 1852 led to the dismissal of the then superintendent and doctor after uncovering, among other things, the physical and sexual abuse of patients, corruption by the management, and frequent drunkenness of the inmates. Doctor Robert Bowie took over the running of the asylum in October 1852 but things did not improve much. In 1861 the Argus newspaper went on the attack, noting mistreatment of the inmates (who were sometimes confined in an appalling device known as ‘the bag’), filthy conditions and numerous other abuses. A brief snippet on 20 November 1861 alluded, without mentioning names, to ugly rumours circulating about Mary’s unfortunate circumstances.

Doctor Bowie, most unwisely as it turned out, decided to prosecute the Argus for libel. The trial ran for nine days. The lurid details were plastered all over the newspapers and in a pamphlet later published by the Argus.

During the trial the sordid and sad details regarding Mary’s pregnancy and its aftermath were revealed. Mary herself was called as a witness, and although she described herself as by then reasonably well, her evidence at times suggested otherwise. Much prurient detail was provided about her encounter with Sloane in one of the cottages, occasioning some laughter in court, as well as doubts about whether she was an entirely innocent victim of her seducer.

All of Melbourne heard how, after Mary had taken refuge with Francis, her older brother (i.e. Andrew), in a great rage, turned up with Doctor Bowie demanding to know who had made Mary pregnant. Mary at first told Andrew to mind his own business, but later admitted Sloane was the father. Bowie was furious and sacked his coachman, who, during these discussions, was waiting outside with the carriage. However Bowie made sure Sloane drove him back home first.

The trial was a disaster for Doctor Bowie and a triumph for the Argus. Witness after witness described the appalling conditions at the asylum and the mistreatment of its inmates. The only count on which the jury found for the plaintiff was in the matter of Mrs. Steele, seemingly because of uncertainty as to her status (whether patient or employee) at the time she became pregnant. The trauma and shame from the trial and surrounding publicity must have been horrific for Mary, on top of the loss of her husband, separation from her children and the death of her baby, not to mention the experience of her confinement in Yarra Bend itself.

Details about the rest of Mary’s life are scanty and it is impossible to tell if she ever fully recovered, or whether she had much contact with Catherine and Thomas Hall who were living in Melbourne from 1866. Mary’s sons, Charles and John, obviously kept in touch with their Bent relatives in Geelong. Both were witnesses at the marriage of their young uncle Francis in 1865. The Pilot Board, noting Mary’s ‘deep distress’ as a widow, made a one-off payment of £10 in 1863-4 and from 1873 she received £20 a year from the Pilots’ Sick and Superannuation Fund. She suffered another sad loss in 1871 when her first born, Charles, who was a fruiterer in Geelong, died from consumption aged just twenty-four.

Mary died at the Melbourne Hospital on 6 July 1879, from typhoid fever, and was buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery two days later, the funeral leaving from the residence of her son John. In stark contrast to the splendid monument commemorating the Halls, there is no headstone.

Hannah, Robert and Richard did not marry, and, as far as we know, left no descendants. And, as I have discovered, there are very few direct descendants remaining from Mary’s line. I therefore make no apology for telling their stories and honouring their memory here.

Featured image: Ralph Snowball. Carriage Drive Insane Asylum, Newcastle, NSW, (Newcastle Hospital for the Insane, Watt Street, Newcastle, NSW), 22 November 1888 (detail). Norm Barney Photographic Collection, Cultural Collections. University of Newcastle

Hi Sally, Gosh, a very long shadow. I’m reading a book called The road to nab end William Woodruff. The hardship and poverty around the cotton mills. Hard to believe how anyone could survive those times. Thanks again for the interesting emails.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Sally – I appreciate your fantastic and illuminating research. Occupational health and safety was rarely a consideration in the years of the Industrial Revolution. I have no doubt Andrew Bent suffered for his craft.

Kind regards,

Matthew

Matthew Byrnes

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Sally for all the incredible research you have done on the Bent family. We are descendants of Benjamin Bent Andrew’s brother, who was also sent to Tasmania as a convict. We look forward with interest to all your emails!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My Grandfather’s name is Norman Bent. Do you know ow anything about his line?

LikeLike

Hi Cassie. I have a Norman Bent (1926-1984) in the family tree. If this is your grandfather he was the great grandson of Andrew Bent’s youngest son Francis Augustine (b. Sydney 1839, d. Geelong 1907) and his wife Julia Sheehan. I’m happy to provide more information, and will try to contact you directly to do so

LikeLike

A nice little read for those who like all things Van demonian…. Also spent a part of my youth in the shadow of the Yarra Bend Asylum.. thanks

LikeLike

Very interesting Sally. We have visited the asylum in Ararat, Victoria, and the conditions for patients from when it was functioning was pretty basic. Thank you for your delving into our family history so comprehensively.

LikeLiked by 1 person