One measure of Andrew Bent’s early success was the amount of real estate he accumulated. He owned several properties in Hobart Town and two small farms at Glenorchy, one granted when he gained his absolute pardon in 1821. From 1828 to 1831 he was also the proprietor of one of the best farms in the lower Midlands, a 1,000-acre property at what was then known as the Cross Marsh.

Bent, by his own admission, was a stranger to ‘agricultural pursuits.’ His purchase of this property appears to have been impulsive and ill-considered and while he put his heart and soul into the venture it was short-lived and he had very mixed success.

The Cross Marsh

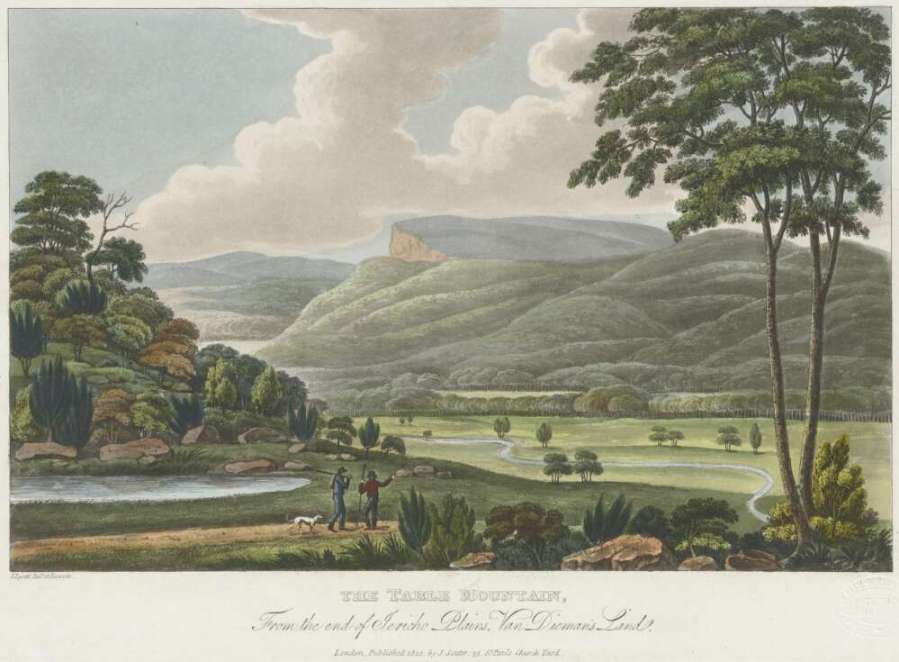

The Cross Marsh comprised the tract of land in between Constitution Hill and Spring Hill, lying roughly between today’s towns of Kempton and Melton Mowbray. When Governor Macquarie passed through the area in 1811 he described it as a broad, fertile, and beautifully picturesque valley skirted by very fine hills. The Jordan River (kutalayna) meandered through it, forming a natural boundary between the territory of the Big River Aboriginal tribe to the west and the Oyster Bay tribe to the east. These peoples were displaced when white settlers moved into the area, attracted by its potential for both agriculture and grazing.

While this painting depicts the Jordan River further upstream, it gives an idea of the lush river flats.

Woodlands

1820-1827 Joseph Whitfield

The original grant, dated 25 July 1821, was to free settler Joseph Whitfield, who emigrated in 1819, originally intending to settle in New South Wales. He changed his mind after seeing Van Diemen’s Land en route, and returned in March 1820 with a letter authorising Lieutenant Governor Sorell to grant him indulgences similar to those already agreed. His declared capital of over £2,500 entitled him to a location of 1,000 acres and the services of five government men.

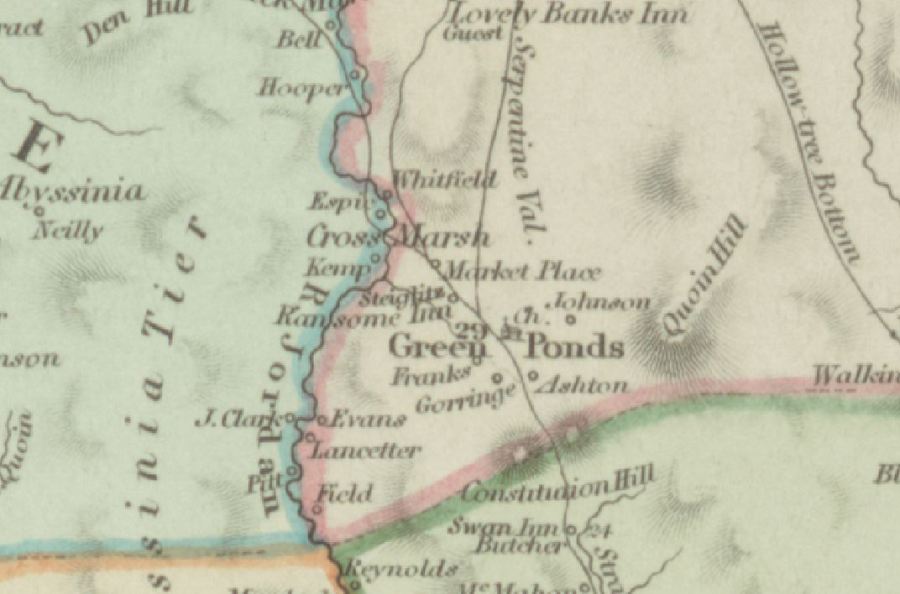

The grant was described rather vaguely as being about 1,000 acres in the district of Green Ponds. The Jordan River formed the western boundary. The southern boundary, starting at a small bend in the river, ran in an easterly direction for 144 chains (approximately 2.9 km), the eastern boundary ran north for 60 chains (1.2 km) and the northern boundary ran from that point across to the river. According to later descriptions the property was 32 miles (approximately 51.5 km) from Hobart Town.

Neighbouring properties included those belonging to Edward Curr on the north and George Espie over the river to the west. Anthony Fenn Kemp’s ‘Mount Vernon’ was already established little further south.

Thomas Scott’s map shows the grants at the Cross Marsh. According to the key, Espie is 3, Kemp 5, and Whitfield 10. Not all the numbers are clear on the map itself, but given that 12 marks James Cobb’s grant, which was on the southern boundary, Whitfield’s property would have to be the one with ‘Cross Marsh’ written across it.

The following map shows the approximate location of some of the homesteads, the Cross Marsh marketplace and Thomas Ransom’s Inn at Green Ponds.

After a short period in Hobart Town (he owned a property in Liverpool Street opposite the then court house) Whitfield moved up to the Cross Marsh and by December 1820 was supplying meat to the Commissariat. He named his property ‘Woodlands.’ In 1826 the Land Commissioners, on their tour of inspection to this ‘delightfully situated’ district, described Whitfield’s property as ‘one of the best arable farms we have seen’ although they noted that its proprietor, while cultivating extensively, spent more money on rum than improvements. This criticism may have been a bit harsh as by 1827, despite set-backs from straying stock, sheep thieves and destructive weevils in the wheat, the property boasted a neat and comfortable weather-boarded house, a four-roomed brick house for servants, a stone dairy, granary, smithy and ‘substantial log barn.’ Whitfield raised some £850 by a mortgage to Edward Lord.

Whitfield was active in the Agricultural Society, was Chief District Constable for Green Ponds (appointed 1822) and was the local pound-keeper. In December 1825 he led an armed party of settlers, convict servants and soldiers in pursuit of bushrangers Brady and McCabe. He cohabited with Fanny Eliza Chambers, a free woman, and, according to his will, had a son in Somerset.

In the early hours of the morning on 8 November 1827 Whitfield died, aged just 37. His will, written the day before, instructed that his property be sold and the proceeds divided equally between his son and Fanny Chambers, who was joint executor with neighbour George Kemp.

The property was duly auctioned at the Cross Marsh in June 1828 when it was knocked down to Andrew Bent’s good friend Bartholomew Broughton for £1,400. One commentator thought this was rather less than its true value.

Bartholomew Broughton

Broughton would have to be one of early Van Diemen’s Land’s most interesting convicts. He was the son of a respectable London solicitor, and before his conviction, had been an officer in the Royal Navy. He arrived in Sydney on the Dromedary in 1819 under a life sentence for burglary, proceeded to Hobart on a ticket of leave soon afterwards, and, after a brief period working for Edward Lord, was appointed clerk in the Naval Office. By 1824 he had a conditional pardon and was living a life of conspicuous luxury (and unashamed adultery) on his beautiful farm at New Town. An enterprising man, he was the first to make wine in the colony, even winning a prize for a sample exported to England.

The disjunction between Broughton’s extravagant lifestyle and his convict clerk’s salary was not lost on newly arrived Lieutenant Governor Arthur, who also soon became aware of a scandalous defalcation amounting to thousands of pounds from the colonial treasury. Broughton’s boss, the Naval Officer E. F. Bromley (who was also de facto colonial treasurer) was suspended from office and Broughton also came under suspicion. In 1826 he was tried for embezzlement but, much to the delight of the anti-Arthur faction, acquitted. It is difficult to determine the extent to which he was actually guilty, but Arthur had no doubts and asked that Broughton’s pardon not be confirmed in England. Just before the trial, Broughton, obviously preparing for the worst, conveyed his property to trustees—Andrew Bent and Robert Lathrop Murray.

Shortly after the auction of ‘Woodlands’ Broughton travelled up to the Cross Marsh to take possession. For some years he had suffered from lung trouble and while there he became ill. The purchase of the new property was, according to one newspaper, ‘too great a stimulus for his debilitated constitution.’ He was conveyed back to New Town but died shortly afterwards. The funeral, on 3 July 1828, left from Bent’s house. A tribute appeared in the Colonial Advocate.

Despite strenuous efforts by Broughton and his father in London, the status of his pardon was still ambiguous at the time of his death. This meant that his will, leaving everything to his mistress Malvina Hobson and her children, was also of questionable validity, a fact which caused no end of trouble later on. Bent, as trustee, immediately set about sorting out Broughton’s affairs. In conjunction with solicitor Gamaliel Butler he advertised the New Town farm for lease, and offered some of Broughton’s possessions for sale. He obviously also went to have a chat with either the auctioneer, or the executors of Whitfield’s will, about ‘Woodlands.’ The terms of the auction had required a 10% non-refundable deposit on the spot, and a further 15% within 21 days, otherwise the property would be resold. Broughton died before making that second payment.

Hi Sally

Another very interesting article, thanks. I wrote a little about Bartholemew Broughton and his farm at New Town in by book Built by Seabrook, with an 1833 sketch and later photo of the house. The piece was mainly about Swanston’s New Town Park, which he built after acquiring the property in the early 1830s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Malcolm. Yes I have seen your book with its lovely illustrations. The trouble I mentioned above happened when Malvina Hobson sold the property to Swanston. Swanston, intending to selling off portions of the property, applied for the grant to be confirmed. Bent entered a caveat. He was obviously under instructions from the Broughton family in London who were keen to assert the rights of Broughton’s sister Charlotte (his heir at law). Bent’s position was that the trust deed set up in 1826 had never been revoked and under that deed Malvina only had a life interest in the property and could not dispose of it. It was the cause of much bickering in the newspapers between Bent and Murray (who supported Swanston and accused Bent of lying). The matter came before the Executive Council several times, both sides having legal representation. The Council appear to have come to no final conclusion yet the grant to Swanston WAS issued, courtesy, one would have to assume, of GA. The Broughtons did not give up, and the dispute was only settled years later after Charlotte’s brother had made a special trip out to VDL.

LikeLike

Thank you Sally – so fascinating!

Kind regards,

Matthew

Matthew Byrnes

LikeLike

Very interesting and engaging…

LikeLike