On 19 July 1828 Andrew Bent—who had grown up in the slums of London, spent his entire working life as a printer, and knew next to nothing about farming—became the owner of one of the finest properties in the lower midlands, a 1,000-acre property at the Cross Marsh. And with becoming modesty renamed it after himself!

It is hard to work out exactly what Bent’s motives were when, as Jorgen Jorgenson put it, he ‘took it into his head’ to purchase Joseph Whitfield’s farm. His own account in the Colonial Advocate probably only tells part of the story.

Broughton had been the successful bidder when Woodlands was auctioned on 17 June 1828, but died suddenly at the Cross March on 28 June 1828. Bent and Broughton had been good friends, and Bent, authorized by a trust deed of 1826, became involved in sorting out Broughton’s affairs. It is not clear whether Bent took the initiative or whether he was talked into making the purchase by the auctioneer or the executors of Whitfield’s will. The property was not re-advertised, and the deal was obviously concluded in some haste. Despite business losses from fines and the denial of a licence for the Colonial Times Bent still appeared to have sufficient capital to purchase ‘Woodlands’ without the encumbrance of a mortgage.

With his career as a newspaper printer looking increasingly precarious he may have seen the rural property as an alternative career path. In the longer term it would also provide a secure future for his ever growing family and a congenial place for eventual retirement. He was, after all, approaching forty years of age. But although he threw himself into his new vocation with great enthusiasm he may soon have come to regret his impulsive decision.

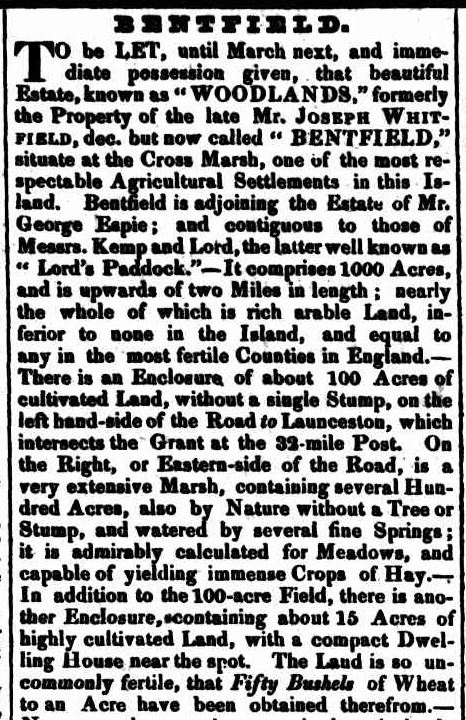

With a printing business still to run, he could not move up to the farm immediately. He advertised for a married couple who understood farming, and for an overseer. He immediately advertised the property to let but as the term was less than a year there were no takers. Allowing for a bit of hyperbole, this long advertisement gives an excellent description of the property at this time.

He did find two blacksmiths to hire the smithy—firstly T. Harris and then Robert Wynn, who came down from Oatlands to take over the business in 1829.

Bad luck continues

Things got off to a bad start. In September 1828 Bent was again imprisoned for a month and so could not go up to the farm. During his confinement the whole island experienced several days of torrential rain. The Jordan River completely inundated the Cross Marsh, destroying several fine fields of wheat at ‘Bentfield’ and dashing his hopes for a yield of 50 bushels per acre. To add to his woes, stock prices took a downturn in 1828.

By year’s end he was seriously contemplating selling the newspaper, but the unexpected repeal of the Newspaper Licencing Act gave the Colonial Times a new lease of life. During the whole of 1829 and part of 1830 he had to divide his time, energy and finances between running the farm, rebuilding the printing business and the ongoing demands of Broughton’s affairs. He was stretched on all fronts. Of necessity he continued to reside in town, although he travelled up to the Cross Marsh—at least a half day’s ride up over Constitution Hill—when he could.

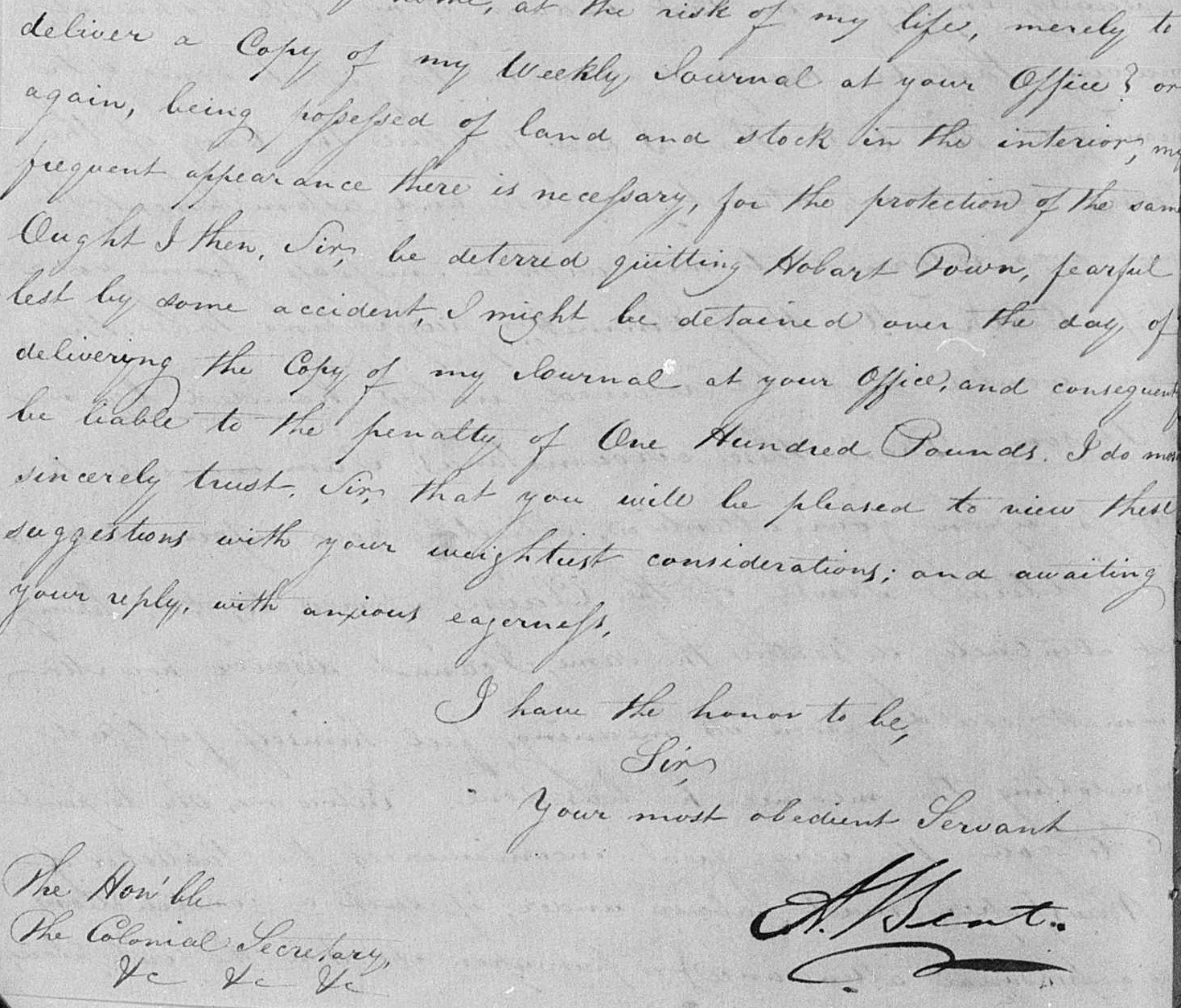

He deposited copies of his newspaper as required by the new Act, sending them in with one of his workmen. But Mr. Emmett (chief clerk in the Colonial Secretary’s Office and the editor sacked by Bent in 1824) informed him in a terse little note that this would not do. They must be delivered by the printer IN PERSON. Bent’s irritation at this bureaucratic nit-picking was obvious in his response. Common sense ultimately prevailed, but only after the Crown Solicitor was called in to interpret the Act.

… being possessed of land and stock in the interior, my frequent appearance there is necessary for the protection of the same. Ought I then, Sir, be deterred quitting Hobart Town, fearful lest by some accident, I might be detained over the day of delivering the copy of my Journal at your office, and consequently be liable to the penalty of one hundred pounds.

For several months from March 1829 the property was regularly advertised to let, but without success.

Farming life

Bent had unlimited free advertising at his disposal and was fully conscious of its power. Possibly no other farmer’s activities have ever been so well documented. Through these ads, as well as some news snippets, we learn of much of the minutiae of farm life. Bent bought grass seeds and sold hay. He advertised stock for sale—a number of remarkably fat cattle (attention butchers) and a flock of about 1,000 fine-wooled sheep (remarkably cheap for ready money—attention emigrants.) One suspects the very same sheep were those advertised a few weeks later as ‘prime fat sheep, fit for the knife.’ Some of this trading was done at the nearby Cross Marsh market where sales were conducted every three months. We know that Bent’s livestock included Suffolk, Devon, and Hereford cattle, Saxon, Teeswater, and Leicester sheep, two teams of working bullocks, and horses. The property also had a piggery and fowl house.

He advertised several times for a fencing contractor but problems with straying stock remained a constant source of irritation. A whole team of recently purchased working bullocks went AWOL, as well as a black sided cow and some cattle belonging to Broughton’s estate. Animals belonging to others were forever getting mixed up in his herds. The government tried to address this perennial problem by an impounding act but this was denounced by the Colonial Times. Bent later described it as a ‘legalized robbing law’ which annihilated settlers with small flocks and herds. A mare belonging to Mr. Fryett was maliciously shot. Hired servant Thomas Archer absconded ‘after destroying and making away with much property.’ Sheep stealer Robert (Paddy) Farrell was sentenced to hang after depredations upon Bent (from whom he stole two ewes) and others.

So much for a quiet life on the farm …

Inter-racial conflict, the roving parties and the military station

Increasing tension between settlers and the first nations people they had displaced led to ever more frequent and violent clashes. In September 1828 martial law was declared. Numerous roving parties scoured the countryside aiming to either capture the Aborigines or drive them out of the settled districts. Parties headed by Jorgen Jorgenson and Gilbert Robertson traversed the Cross Marsh area during 1829. In February 1830 Bent’s neighbour George Espie told the Aborigines Committee of increasing outrages by the Aborigines, referring to them as ‘audacious’ and ‘treacherous’ and holding out little hope for successful conciliation. In August 1830 James Hooper was killed at his farm at nearby Spring Hill. Just a few days later

a small tribe of about twelve [Aborigines] made their appearance … at the Cross Marsh, upon Mr. Curr’s farm, where they for some time chased two of Mr. Bent’s farming men, who fortunately made their escape, after firing upon them and taking some of their spears. This is supposed to be part of the same tribe that murdered Mr. Hooper (CT 27 Aug 1830)

There was a military station at Bentfield, which was probably in use during the time the Brady bushranger gang was active. In August 1829 Robert Wynn advertised that he was about to open a farriers and blacksmith’s shop at Bentfield ‘adjoining the Military Station.’ It was obviously still occupied in December when one soldier in a military party headed there was murdered on the way. There seemed to be soldiers in residence in July 1830 when Jorgenson and his party, having ascended the Quoin, went down to what was described as a soldiers’ hut just under the Quoin and on the road to the Lakes. Yet only a month or so later, on 22 August, the Colonial Times announced that the military station at the Cross Marsh was to be AGAIN established. ‘Mr. Bent had received proposals which he intended to comply with, by which means the former dwelling of the Military will be acceded to them.’ A letter in the Tasmanian newspaper indicates that the military station had been disbanded by November 1831.

‘A person on horseback’

Convict writer Henry Savery has left us a charming if slightly tongue in cheek pen picture of Bent on his farm in 1829. This appeared in the Colonial Times in the series of satirical sketches entitled ‘The Hermit in Van Diemen’s Land.’ Savery was confined for debt in Hobart Town gaol at the time of writing, so some allowance for poetic licence should be made.

property sold

By the end of 1829 Bent was in dire trouble. Several libel prosecutions, due in part to Savery’s pungent satire, were imminent. In December Bent advertised the printing business and Colonial Times for sale by auction. Although he said his ONLY reason for doing so was his ‘long-contemplated intention to retire with his family upon his Farm Residence, in the Interior’ few would have believed him.

Bent handed over the printing business to Henry Melville at the end of February 1830. For a while he appears to have spent rather more time at ‘Bentfield’ although it is not clear whether the whole family (there were by then six children) ever went up there to live. Although the sale to Melville had realised £900, he was hit with damages for £180 for libels and doubtless even more in legal costs.

He seemed unable to settle. Just a few months after relinquishing the paper he was again seeking a tenant (or a buyer) for ‘Bentfield.’ He had decided to reopen his Elizabeth Street premises as a ‘wholesale and retail agency and commission warehouse’ although he appears not to have actually done so at this stage. Captain Dumas of the 63rd Regiment was said to be interested in buying the farm, but nothing came of this.

In November 1830 Bent upped the ante, offering the property for sale by private contract, if not previously let to a respectable tenant. Long and glowing advertisements also appeared in the Sydney Monitor throughout January 1831. His ‘views and pursuits’ he said, confined him ‘chiefly to Hobart Town … preventing his personal attention to the capabilities of his Estate.’ Reading between the lines one would have to assume he was in financial trouble and, despite having thrown himself heart and soul into rural life, the gloss had definitely worn off and he saw little prospect for future success as a farmer.

By March, perhaps in desperation, as by this time he had probably committed himself to importing expensive new printing equipment, the property was listed for auction. If this indeed took place, the property must have been passed in because in April he offered to sell off small portions of between 100 and 500 acres. He said that several ‘liberal offers’ had already made by people interested in erecting a water flour mill, an inn and a brewery. He was probably making this up as Arthur, while visiting the district, had apparently said it would be a good site for ‘a Public Inn, Brewery, or General Store.’ Finally, a month later, probably after private negotiation, he found a buyer.

After the sale he commenced slaughtering his herd and, obviously in need of some cash flow, was selling cut-price prime fat beef from the old Colonial Times office. His attempt to become a gentleman farmer had not turned out too well, but perhaps he took some satisfaction in seeing his name recorded on the instrument of conveyance as ‘Andrew Bent, Gentleman.’

1831-32: JOSEPH HONE

Bentfield was purchased by Hobart solicitor Joseph Hone for £1,800. There was a bit of history between Bent and Hone but it did not stop them doing business. Hone had arrived in 1825 and was appointed Master of the Supreme Court. In 1826, while acting Attorney General (a position for which Arthur considered him quite unsuitable on a permanent basis), he successfully prosecuted Bent for libel. There was considerable irony in this as Hone’s brother William Hone was a well-known London publisher and bookseller whose acquittal on libel charges in 1817 was celebrated as a great victory for freedom of expression. Joseph Hone’s unfortunate mannerisms and air of self-importance meant that many in Hobart Town laughed at him behind his back, and he had been savaged several times by Savery in the Hermit sketches in Bent’s paper.

In 1829 Hone had been granted 2,560 acres adjoining ‘Bentfield’ on the eastern side and had at some point acquired other property nearby. He borrowed £1,000 of the purchase money for ‘Bentfield’ on mortgage and asked the Colonial Auditor, Boyes, to lend him the rest. Hone offered no security whatsoever so Boyes, rather disgusted, did not oblige. Referring to Hone as ‘that stupid lag killer,’ Boyes also confided to his diary that, according to local gossip, Hone was ‘over head and ears in debt’ and would soon be a ruined man. There may have been some truth in this talk as less than a year later it was reported that Mr. Hone had disposed of his beautiful estate at the Cross Marsh for £4,000. He continued, at least for the time being, to lease Edward Curr’s nearby property.

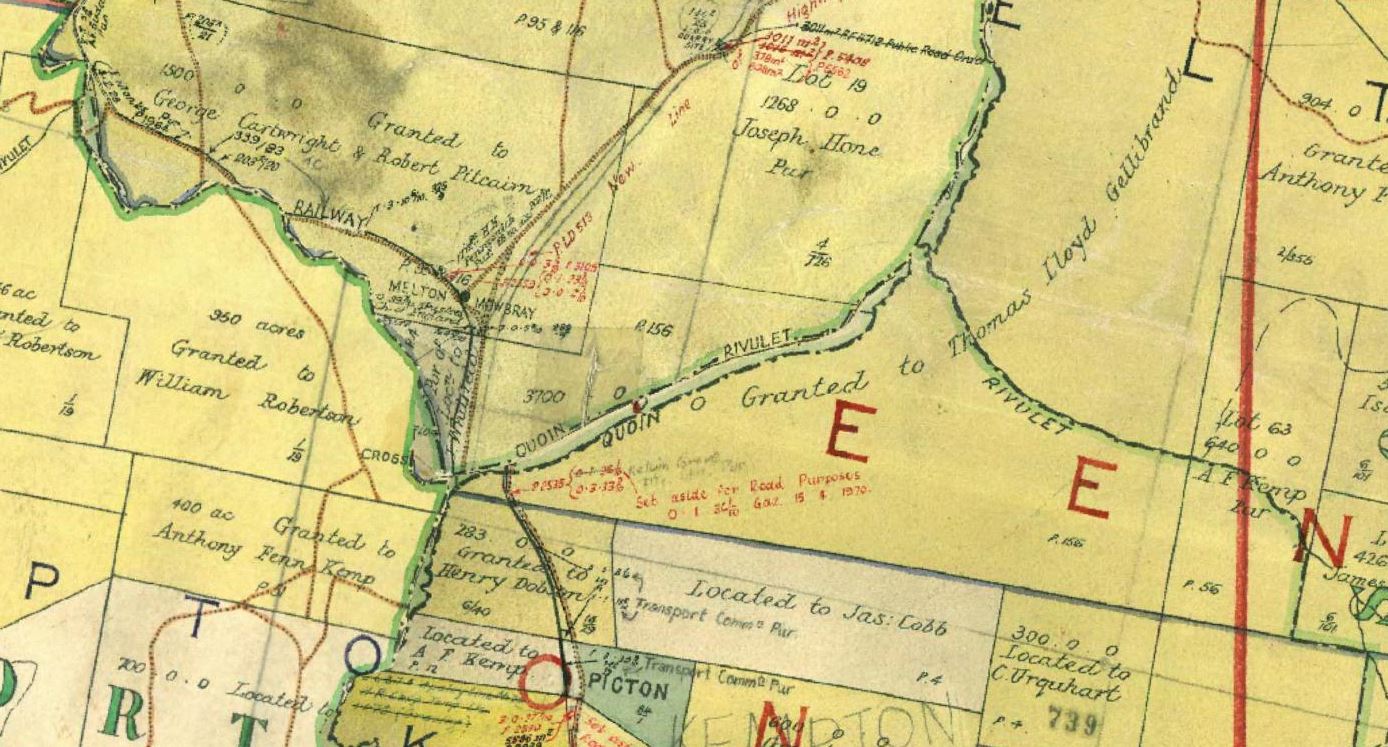

1832-1852 BENJAMIN BERTHON

The purchaser was recently arrived former East India merchant Benjamin Berthon. He had better luck than the previous owners and during his twenty years at the helm the property flourished and increased in size. Berthon’s initial purchase from Hone in April 1832 consisted of Whitfield’s 1,000 acres plus another 1,295 acres (for which, combined, he paid £2,000) and in addition Hone’s own nearby maximum grant of 2,560 acres. By 1838 Berthon had also acquired Curr’s grant. He purchased further land from Hone in 1838 and 1839. The estate reverted to its original name of ‘Woodlands’ and, commencing in the 1840s, Berthon built a substantial homestead from brick and local sandstone which still stands on the eastern side of the Midlands Highway and has been recently restored. Whitfield’s original weatherboard homestead appears to have been much closer to the river, although its precise location has not been identified.

In the 1843 census Berthon and his family were recorded at ‘Woodlands’ in a stone dwelling, although the previous year it was said to be of brick. There were in all 31 persons on the estate in 1843.

LATER OWNERS

In 1852, two years before his death, Berthon sold ‘Woodlands’ in parcels, realising over £20,000. The main portion, which included the stone homestead, was purchased by a Thomas Brown and later became part of the valuable portfolio of lower Midlands properties owned by Samuel Page. From the Page family it passed to Harry Batt whose descendants still live on the property.

MELTON MOWBRAY HOTEL

On 21 May 1859 Samuel Blackwell, who had been licencee of the nearby Royal Oak inn for some years, announced the opening of a new hotel at the junction of the main road to Launceston and the Bothwell road. He named the spot Melton Mowbray after his birthplace.

The Melton Mowbray Hotel still stands on land which was once part of ‘Bentfield.’ This property deed, relating to an earlier transaction for the same land in September 1854, shows the 519 acres purchased by Blackwell, which included part of Joseph Whitfield’s original location.

Fascinating! Eagerly anticipating the next episode.

LikeLike