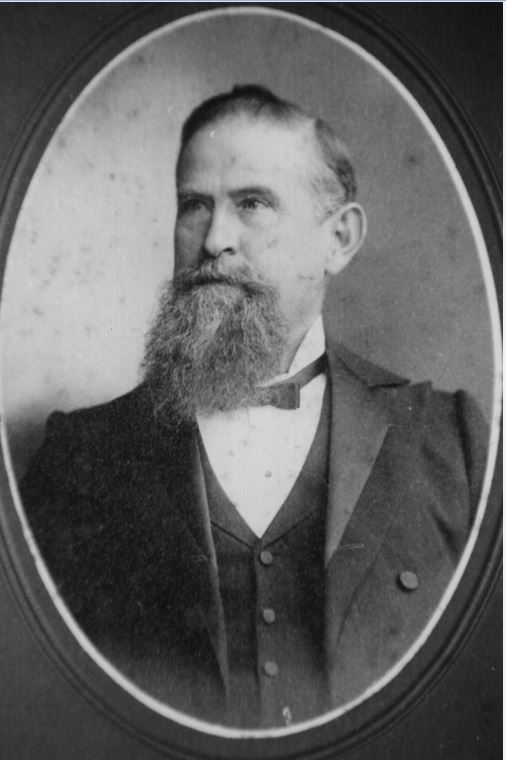

Benjamin Bent, the middle of the three Bent brothers, arrived in Australia, like his two siblings, as a transported felon. He had his first encounter with the magistrates, and first taste of prison, at the tender age of twelve or thirteen. In 1818, aged just twenty-four, he left England on the Morley to commence his SECOND term of seven years’ transportation. Fragmentary snippets relating to Benjamin’s troubled youth provide virtually the only clues we have to the early life of the three brothers growing up in the overcrowded, crime-ridden, gin-soaked but socially vibrant purlieus of St. Giles in the Fields, in the area around Drury Lane.

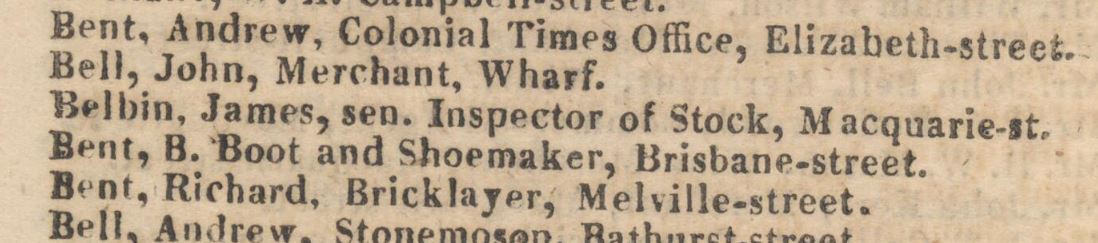

Andrew Bent has left us a substantial legacy in print, Richard a small one in brick. It could perhaps be said that Benjamin achieved nothing particularly noteworthy after arriving in Australia, but the extent to which he turned his life around is in itself remarkable. After serving his time without incident in New South Wales Benjamin joined his brothers in Hobart Town. He married, had a family, sensibly eschewed political involvement, and earned an honest living as a shoemaker until his untimely death in 1843. Being transported was probably the best thing that ever happened to him.

St. Giles in the Fields

Benjamin was baptised at the parish church of St. Giles on 31 December 1794, recorded in the register as the son of Anthony and Elizabeth Bent. This may be a transcription error as the entries for his older siblings Elizabeth and Andrew both name the father, quite clearly, as Andrew.

We know nothing more of Benjamin until October 1804 when, only ten years old, he was apprenticed as a poor child of the St. Giles parish, to William Fowler, of Spitalfields. Fowler was a ‘harness maker and enterer.’ This has nothing to do with horses, but relates to the setting-up of silk weaving looms. For reasons which are unclear the master refused the arrangement and returned his half of the indenture to the parish authorities. Was Benjamin too little or too naughty, or was it because, later on, he was said to be, like his two brothers ‘awkwardly made?’ Because this apprenticeship did not proceed Benjamin probably spent far too much time on the streets.

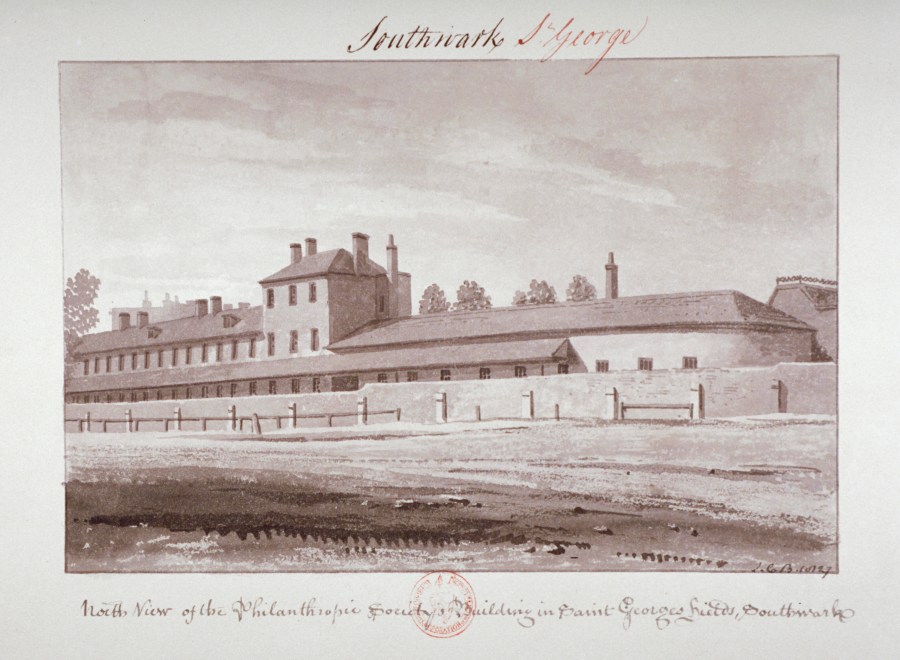

Philanthropic Institution

By late 1807 young Benjamin, probably with nobody but his older brother to take care of him, was in serious trouble with the law. He had been a member of a gang of juvenile thieves who for several months had ‘carried on a complete system of depredation’ and sound like something straight out of Oliver Twist. Nine of the culprits were sent away to sea. After spending five weeks in Cold Bath Fields prison Benjamin and one other boy, Isaac Hancock, were recommended to the care of the Philanthropic Society.

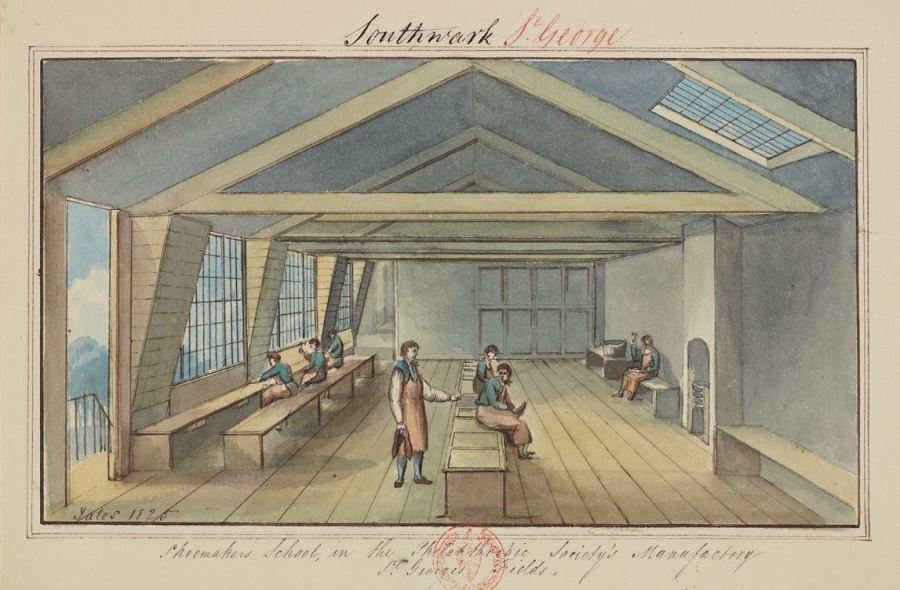

This body had been established in 1788 to care for children who were living on the streets, children of convicts, and youngsters who were themselves criminals. The children, both boys and girls, were given a rudimentary education and taught a useful trade. The Society’s reformatory, usually referred to as the Philanthropic Institution, was in St. George’s Fields in Southwark.

Benjamin was admitted on 29 January 1808. The admission register describes him as an orphan of the Parish of St. Giles who had no relations apart from his two brothers. His mother was remembered as ‘a woman of bad character.’ Benjamin was ‘completely ignorant’ (i.e. uneducated) but his disposition seemed favourable. Isaac, who was blind in one eye, was at various times described as ‘sharp and artful’ and a ‘very hardened’ boy. His mother, after being deserted by Isaac’s father, eked out a living as a washerwoman in Cockpit Alley, just off Drury Lane. This laneway was very close to Stewart’s Rents, where an Elizabeth Bent, likely to be either Benjamin’s mother or older sister, had died in February 1804, shortly after the apprenticeship arrangement foundered.

Benjamin initially settled down under the Philanthropic Institution’s regime of tough love and watered-down milk. He was apprenticed to Mr. Mills, the shoemaker.

He later made several escape attempts, always with other boys, sometimes gravitating back to his old tribe in Drury Lane before being found and brought back to the reformatory. The bumbling do-gooders sent to search for him seemed genuinely fearful for their lives when entering St. Giles and encountering the ‘set of wretches’ they found there. Benjamin’s final escape occurred in 1811, just one day after Andrew left the country on the Guildford, so was possibly motivated by the knowledge that his brother was leaving him for good.

Conviction

Apart from being a day too late, other things went horribly wrong. The three runaways took with them some clothing stolen from the tailor’s workshop. Benjamin soon parted company with the other two, who eventually returned to the reformatory. They appeared later as witnesses at the trial of a man accused of receiving the stolen clothes. This gives a pretty full account of all the boys got up to. At first they said they did not know where their comrade Bent was, but after a dressing down from the judge, admitted he was in Newgate ‘for thieving.’

It was a challenge to find Benjamin in the Newgate records for 1811 because he had been convicted under an alias. Once discovered, the entry for a William Wood of the right age helpfully identified him as a runaway from the Philanthropic Society and ‘brother to Andrew Bent, transported.’ It was of course only four months since Andrew had been taken from Newgate to the hulks.

Benjamin had been caught red-handed stealing cotton stockings from outside a hosier’s shop in Bishopsgate Street. The trial report paints a vivid, indeed hilarious, picture of Benjamin (aka William) rolling around in the gutter with the fellow who literally ‘collared’ him, biting the man’s hand, and being sooled on by a number of ‘loose people’ (girls) who were at the same time adroitly removing the evidence from his pockets.

He was found guilty and sentenced to seven years’ transportation. He appealed to the Society to take him back or to interfere on his behalf, but the committee decided he was a hopeless case and left him in the hands of the law.

The Hulks

As a young first offender (just seventeen) Benjamin was not shipped off to the other side of the world. He served six years of his seven-year sentence on the Zealand hulk (later the Retribution), where brother Andrew had so recently been. There was a veritable revolving door in Newgate and on the hulks.

As a shoemaker, Benjamin may have been excused from hard labour in the dockyard and allowed to remain on board the vessel mending and making shoes. During the first half of his sentence conditions were nonetheless dire, especially for one who was still an adolescent. There was no separation of the prisoners into different classes and little hope of reformation when, as the chaplain observed, old and young, the hardened and the unfortunate, were all promiscuously huddled together, and ‘vicious propensities indulged without restraint.’ Over this period there were, on average, 430 convicts on board, including 24 boys, one as young as twelve. Things improved markedly when the vessel was partitioned into smaller cells and some classification introduced, along with better night supervision, or at least they did according to the Superintendent of the Hulks, John Henry Capper, who also noted the improved health and conduct of the convicts in a report in 1816.

Benjamin obviously behaved well and, in September 1817, a year before his sentence would normally have ended, received a free pardon.

Convicted again

It is perhaps not surprising that just eight months later he was again before the courts (this time the Middlesex Sessions of Peace) for delicately removing a handkerchief from the pocket of a young gentleman named Charles Spencer Stanhope. Benjamin and his co-accused, sixteen-year old William Welch, also a native of St. Giles, were sentenced to seven years apiece. By this time Benjamin’s older brother Andrew was beginning to establish himself in Hobart. He was conditionally emancipated, married, and employed as Government Printer. If he had managed to stay in touch with Benjamin, his sibling may not have been too dismayed when contemplating his future. Prison records from this time describe Benjamin as just over five feet two, ‘stout made’, with a dark complexion, brown hair and grey eyes. The description on his certificate of freedom (1825) is similar but adds that he was pock-marked.

Fresh start in New South Wales

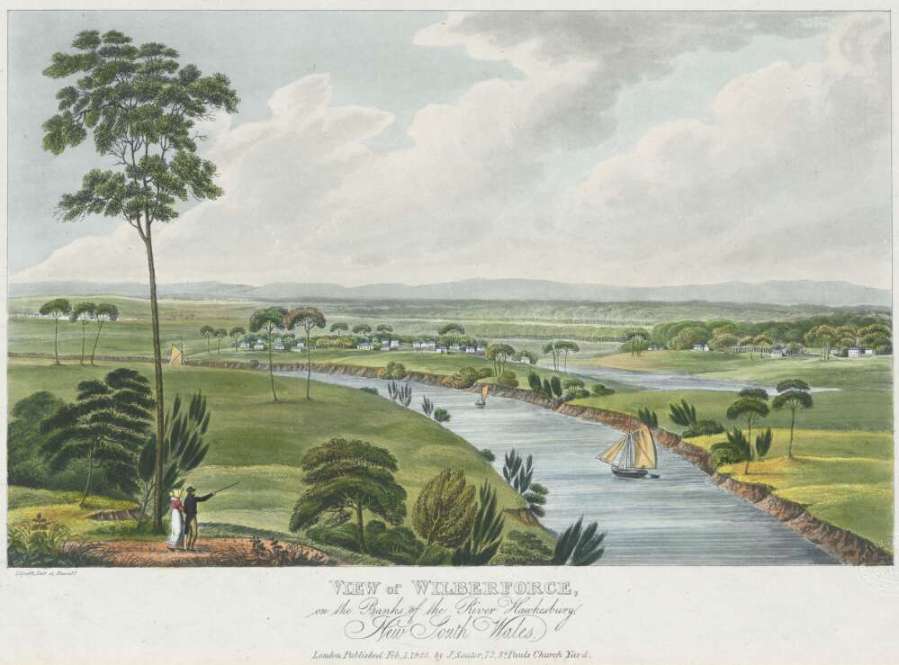

The Morley arrived in Sydney on 7 November 1818, after a very quick voyage with no stop-overs. Only one convict died on the passage and the other men all arrived in good health. Benjamin now had reason to be grateful to the Philanthropic Institution. Although he had not completed his shoemaking apprenticeship, he had enough skill to be assigned to Wilberforce settler Paul Bushell.

Bushell, an emancipist who had survived the horrors of the second fleet, was an interesting man and a humane master. He had become a leading citizen of the small Hawkesbury community and had numerous interests in addition to farming. These included a shoemaking business which employed, over the years, a number of convict shoemakers. Benjamin, removed from the cold, dark, overcrowded, dirty world of London and the hulks flourished in what must have seemed a veritable paradise of sunshine, space, clear air, clean water, and, probably for the first time in his life, kind treatment. He served Bushell ‘faithfully’ and in 1823, supported by the master’s strong recommendation, was granted a ticket of leave. By 1825 he was free.

Hobart Town

Soon afterwards Benjamin joined his brothers in Hobart Town. He is first recorded there in 1827 as witness to a business document for his bricklayer brother Richard. Although it must have been advantageous to both the younger brothers to have their older sibling well established in Hobart Town, relations between them were hardly amicable if one can believe Jorgen Jorgenson, who knew them all. They hardly ever spoke to each other. Andrew called his brothers ‘d—-d rascals’ and they apparently had a similar opinion of him!

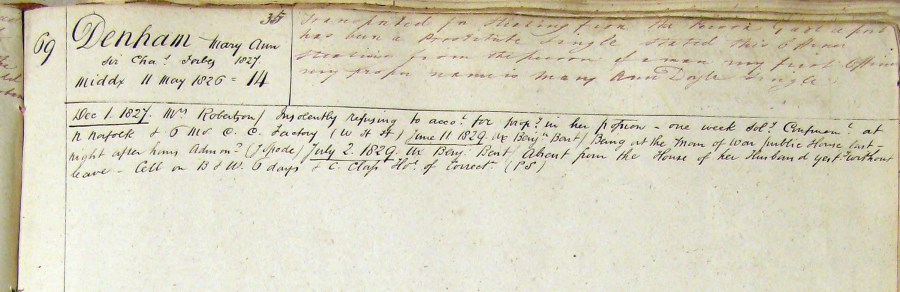

On 16 March 1829 Benjamin married Mary Ann Denham (or Doyle), aged 19, and still a convict. Mary Ann, convicted in London, had been sentenced to fourteen years’ transportation for stealing a watch, chain and key from a man’s person. She arrived in Hobart Town early in 1827 on the Sir Charles Forbes. She strenuously denied ever having been a prostitute. Initially rather trouble prone, spending six months in the Female Factory’s crime class not long after her arrival, Mary Ann settled down after her marriage and especially after the children came along.

She and Benjamin had six children who were baptised – Mary Ann Jane (1830), Jane (1833), Benjamin (1836), Samuel (1837), James Joseph (1840) and Paulina (1842). There is also DNA and documentary evidence of another daughter, Amelia, born around 1828, before the marriage. Benjamin plied his trade as a shoemaker, initially at the eastern end of Brisbane Street (no. 3). In 1829 he assigned his interest in this property to Roger Gavin for £90 and moved to rented accommodation in Argyle Street. The family was recorded there in the 1842 census. Benjamin died from dysentery on 15 April 1843 when his youngest child, Paulina, was still an infant. By this time his two brothers had moved away from Van Diemen’s Land.

Benjamin’s brother Andrew made an interesting observation in Bent’s News 16 July 1836:

We suggest, that there should be some Establishment here, similar to the Philanthropic Society at home, for the employment of such juvanile [sic] offenders in the Colony, as could not otherwise be better disposed of; and for this purpose we would suggest, so soon as a new Gaol be built, the present old one be converted into a building for a Philanthropic Society, not only for the reception of such children, but likewise for all orphan boys, who may wish to learn a trade. We understand there are upwards of one hundred boys at the penal settlement at Port Arthur.

Postscript

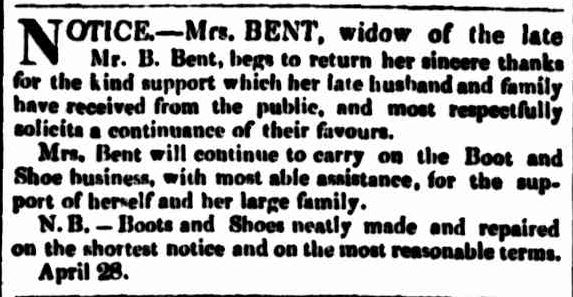

After Benjamin’s death Mary Ann advertised she would continue the boot and shoe business.

She was aided by Benjamin’s assistant Edmund Wilson, who, as a resident of the house, was the informant at her husband’s death. Wilson had arrived free with his mother and two siblings in 1830, to join his father (convict per Commodore Hayes 1823). Although he was considerably younger than Mary Ann they soon developed a relationship, which is understandable given she had been left with six children to care for. They moved to Launceston and then, probably in 1846, to Port Phillip. They were certainly there by around 1850. Mary Ann and Edmund had a further four sons together. There appears to have been no marriage although Mary Ann’s surname was recorded as Wilson when she died in Richmond on 7 December 1884. All the children she had with both Benjamin and Edmund are listed on her death certificate.

Samuel Bent

There has been some confusion in online family trees about Benjamin’s son Samuel, who had a very successful career as a school teacher in New South Wales. He became a highly respected headmaster – quite an achievement for the son of a humble convict from the London slums. Samuel’s death certificate names his father as Andrew Bent, although the mother is recorded as [no Christian name] Denham. The informant was a son in law who obviously got muddled. It is clear from Samuel’s testimony at the death of his brother James Joseph in 1873, that he was Benjamin Bent’s son. Additionally, there is no Samuel in a definitive list of the children of Andrew and Mary Bent printed and annotated by Andrew Bent himself.

Samuel’s story is a fascinating one. For reasons which are almost impossible to fathom, Mary Ann left her son (and possibly some of the other children) behind when she moved to Victoria. In 1847 Samuel’s left arm was badly injured in a machinery accident at Norfolk Plains. The very first volume of the Medical Journal of Australia has a report on the subsequent amputation. In 1850 the Rev. Davies, finding this obviously bright lad was destitute and living on charity at Longford, applied for this boy, the son of an orphan and now near enough to being orphaned himself, to be admitted to the Queens Orphan School in Hobart. The correspondence mentions that he was ‘the nephew of old Andrew Bent who was the first printer of a newspaper in the Colony.’ Samuel became a rare success story emanating from the Orphan School. More information can be found on the Friends of the Queen’s Orphan School website. It is worth noting that Edmund Wilson (junior) of Melbourne, attended Samuel Bent’s funeral as one of the chief mourners.

Benjamin’s three daughters all married in Victoria and there are numerous descendants. There are also many descendants from Samuel and his wife Margaret Paton, who had a large family in New South Wales. If any of you are reading this blog post please do get in touch.

Thanks to Patricia O’Neill (London Archives) for commissioned research at London Metropolitan Archives and Surrey History Centre.

Further reading:

Louise Wilson. Paul Bushell: Second Fleeter. South Melbourne, L. Wilson, 2010 (includes notes on many of Bushell’s convict workers, including Benjamin)

Papers relating to the convict establishment at Portsmouth, Sheerness, and Woolwich: viz. two reports of John Henry Capper, Esq. superintendent of the several ships and vessels for the confinement of offenders under sentence of transportation; dated 16th October 1815, and 26th January 1816: and also, instructions from the Secretary of State’s Office, to the said superintendent; dated 23d August 1815. HC papers 1816 10, 19

Hi Sally

The Bent story continues! Very interesting to read what happened to a very distant relative. One wonders what would have become of the Bent family if they had remained in England. Are you going to publish their story? I’m still following my Austin story.

LikeLike

I strongly suspect they would have ended up on the gallows as Andrew so nearly did in 1810-11. The experiences of Andrew’s fellow burglar Philip Street and his older brother Thomas, who both came from a rather better family background, are a case in point. Thomas was transported for 7 years, did extremely well in NSW and died back home in England a wealthy man. Philip, when convicted with Andrew Bent, was not transported, but served a year in prison and was then pardoned. In 1816 he was convicted for more burglaries and was hanged. (see post on Philip Street on this website)

LikeLike

Fantastic read Sally! I enjoy every chapter!,

LikeLike

I believe I am a direct descendant of Benjamin Bent and Mary Ann Denham. I believe that Mary Ann Jane Bent (Mary Ann Denham’s daughter) was my great, great grandmother. She married William Duff in 1852 in Melbourne.

LikeLike

Thanks for getting in touch. You don’t have to answer this but would your connection by any chance be through their son William Walter who became an actor and changed his name to Forbes?

LikeLike

Yes, I am the great grandson of William Walter DUFF and the grandson of Lawrence Walter Gordon Forbes DUFF.

LikeLike

My Great Grandmother was Louisa Elizabeth Rieger who had a relationship with David Duff who was the son of William Duff and Mary Ann Jane Bent. David Duff was born in Sandhurst in 1861 and moved to Wagga Wagga, NSW. David and Louisa had 6 children. For an unknown reason David Duff changed his name to David Doyle some time after 1890. David and Louisa’s children all went by the name Doyle and their first two children were registered with the surname Duff.

David and Louisa never married because Louisa was previously married to a Richard Coles. It’s interesting to note that David used the name Doyle as that appears to be the name of his Grandmother Mary Ann Denham.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for posting this. It will be of great interest to some of Amelia Bent’s descendants who have thought (and I agreed with them) that David Doyle must have been David Duff. There is no baptism record for Amelia but DNA evidence suggests she was a daughter of Benjamin and Mary Ann. Your information further supports that scenario. I love the way collaboration between descendants can help unravel family mysteries.

LikeLike

Hi Sally and thanks for your informative research. Benjamin Bent (b.1836) the son of Benjamin and Mary Ann deserted from the army in Launceston in 1848 and it was reported he was in the company of his Mother and a young child who had just arrived from Adelaide and they were going to Hobart but it is supposed they went to Port Phillip. Benjamin then assumed the names of Henry Benjamin Bent or Henry Wilson. He died intestate in NSW in 1913 then in 1917 a Solicitor advertised for a Sister of Benjamin namely an Amelia Bent to contact him re her share of the estate. Which leaves little doubt that Amelia was the the daughter of Benjamin and Mary Ann and that Benjamin (junior) never married which is contrary to some online family trees.

LikeLike