In 2024, as Australia celebrates 200 years of a free press and independent journalism, there are several people we can thank:

- Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane—who took unto himself perhaps rather more credit than was justified for what he actually did.

- Saxe Bannister, then Attorney-General of New South Wales and advisor to Brisbane.

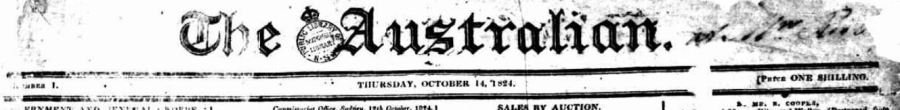

- Barristers William Charles Wentworth and Robert Wardell who established Sydney’s first independent newspaper, the Australian, on 14 October 1824.

- Last, but certainly not least, Hobart Town printer and publisher Andrew Bent.

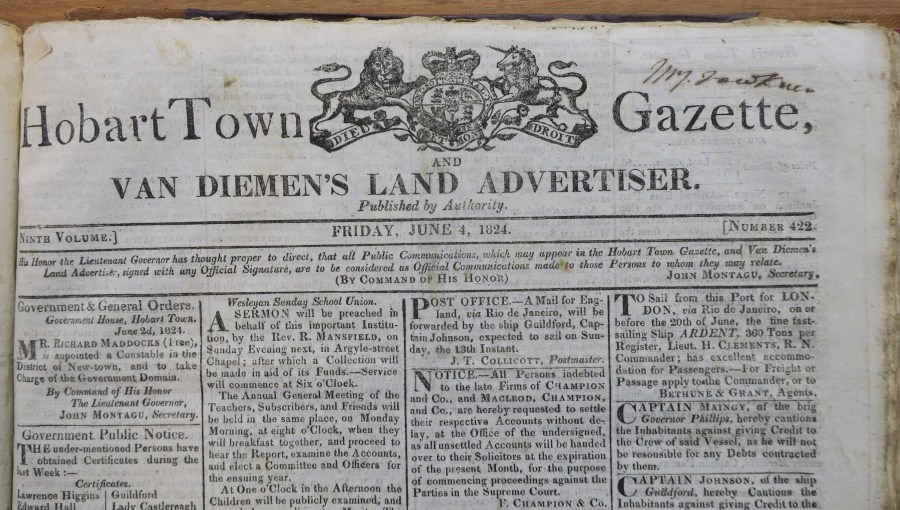

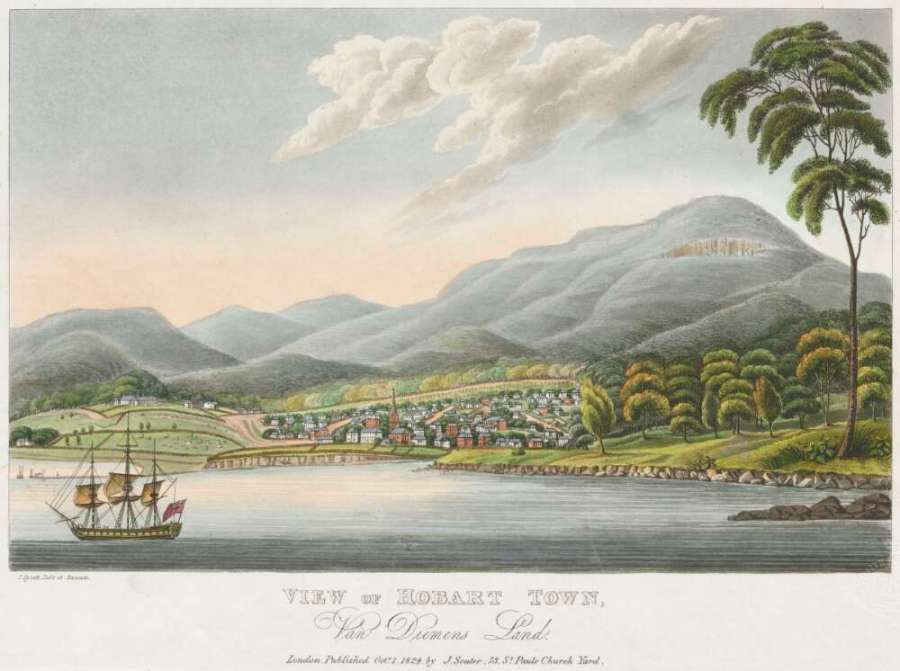

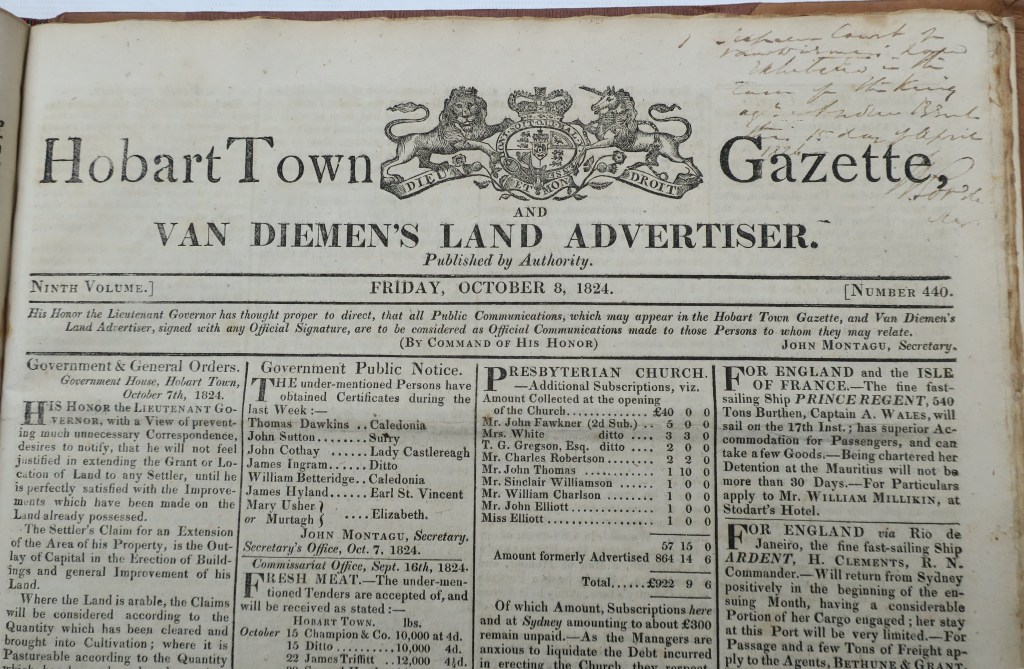

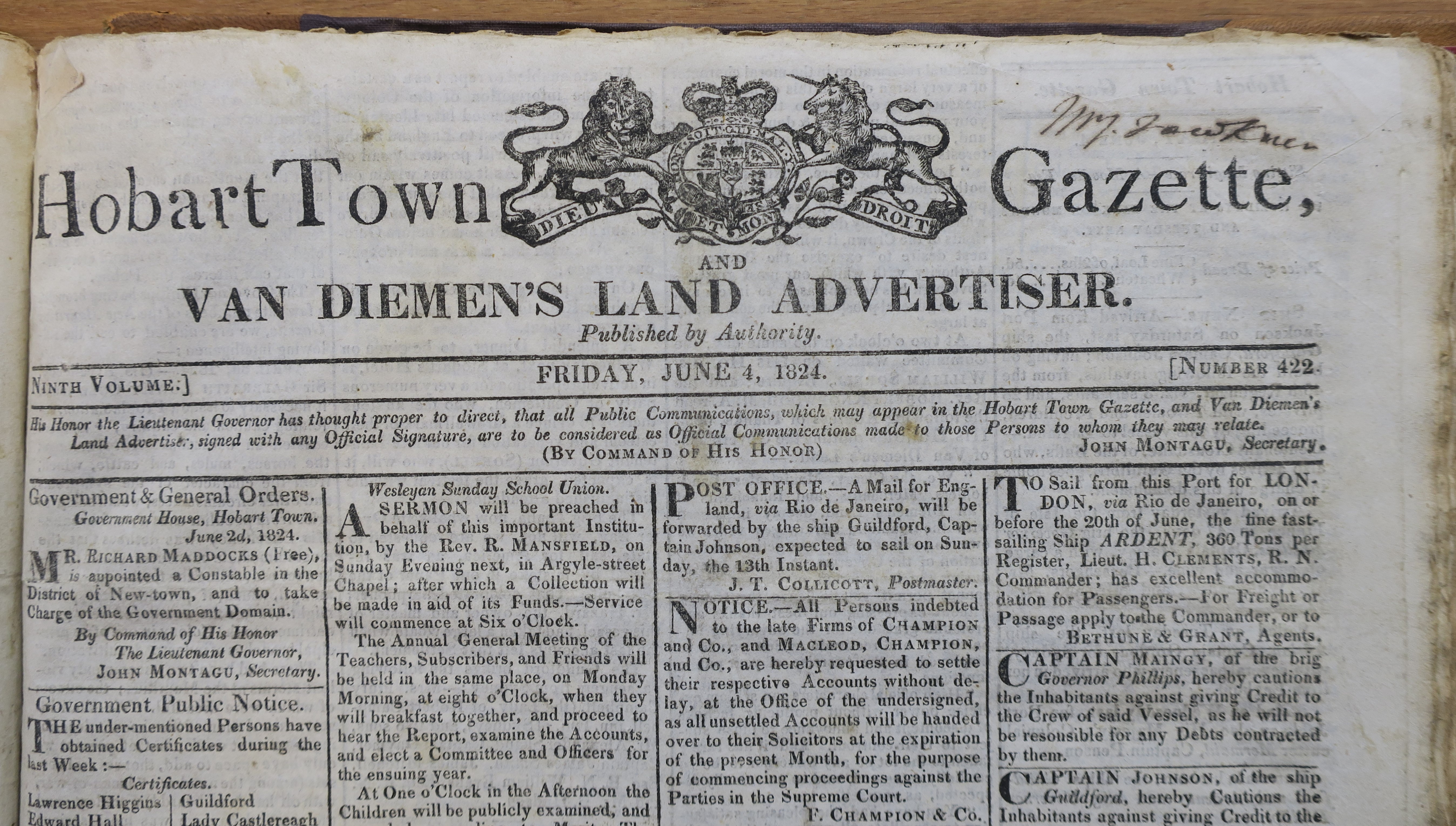

On 4 June 1824, some four months before the first appearance the Australian, Andrew Bent printed the first newspaper in the Australian colonies to be uncensored by government—no. 422 of the Hobart Town Gazette.

Background

The early newspapers of the Australian colonies were not subject to the same repressive taxes and regulations which had been introduced in England to control political dissent although, being in convict colonies, they were under strict control of government. They had a rather ambiguous status. While the printers, the Howes in Sydney and Bent in Hobart, took the profits from newspaper sales and carried any business risk, the papers were at first printed with equipment owned by government, were the official means of government communication, and were subject to government censorship. The publishers also held the position of Government Printer. In both colonies the proofs were vetted each week before publication. Bent himself described that process in the evidence he gave to Commissioner Bigge in 1819.

Bent’s first uncensored newspaper appeared within days of him sacking his government-appointed editor Henry James Emmett. Concurrently he appears to have fast tracked a process already underway to give him private ownership of newly arrived printing equipment. And, whether by accident or design, this throwing off the shackles also happened within three weeks of the arrival of the new Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, Colonel George Arthur.

A standoff soon developed between the recalcitrant printer and the governor, and the flow-on effects of this fed directly into decisions which Governor Brisbane made in Sydney later in the year. In January 1825 Brisbane rather belatedly informed his superiors in London, that he had decided to experiment with ‘the full latitude of the freedom of the Press’. The proprietors of the Australian had not asked permission to publish and Brisbane declined to intervene. He also complied with a request from Robert Howe, printer of the Sydney Gazette, to remove the censorship which had applied to that paper since its inception in 1803.

Brisbane did not mention Andrew Bent or Van Diemen’s Land, but Saxe Bannister’s note recommending the lifting of censorship from the Sydney Gazette had referred specifically to ‘my former opinion, at some length, on the same subject and reported when the case of the Hobart Town Gazette was referred to me’.

Tensions develop May-June 1824

Emmett had only been in the editor’s job a few months when the trouble began. He had been appointed by Lieutenant Governor Sorell in December 1823. At this time Bent was moving into a new purpose-built printing office, announcing plans to substantially increase the size and scope of the Gazette (including opening its columns to correspondents), and anticipating becoming owner of new printing equipment once he repaid the nearly £400 which had been advanced to him by government for its purchase. After years of struggle to improve his newspaper he was, according to one anonymous local, on the point of succeeding ‘beyond all expectation’.

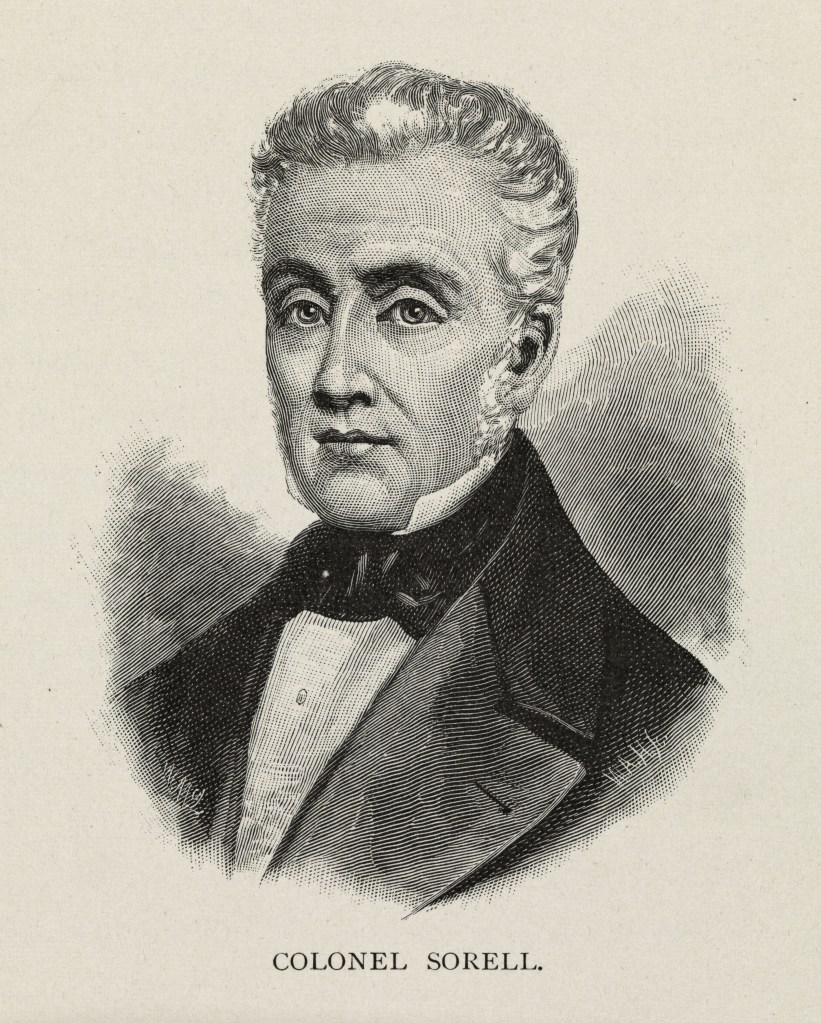

The editorship was only one part of Emmett’s duties, as he also replaced Thomas Wells as chief clerk in the Secretary’s Office. Sorell obtained Bent’s agreement to pay Emmett £100 a year. Emmett (and Sorell too for that matter) had little understanding of what Bent needed and expected from his editor. Tensions erupted in late May in the volatile atmosphere induced by Arthur’s arrival. Almost everyone in Hobart was on edge.

Emmett was nervous about an upcoming libel trial in the newly opened Supreme Court. The offending material had been printed in the Gazette under his watch, and the prosecutor was Robert Lathrop Murray, who was soon to become closely involved with Bent’s paper and about whom there will be more later. It was the first public clash between Murray and east coast settler George Meredith (the first named defendant and a man with an ego to rival Murray’s) and arose out of the public debate about whether Van Diemen’s Land should become independent of New South Wales.

Emmett, worried about his legal liability, wanted Bent to employ a court reporter. Emmett appeared to have neither the time nor the inclination to perform this duty himself. It seems that Bent, who was probably also worried about the impending trial, was having to attend the court, as well as having the whole burden of correcting and arranging the contents of the newspaper. The printer, stretched financially by his recent business expansion, with repayment of the loan looming, and already dissatisfied with the performance of Emmett as editor, was naturally unwilling to spend any more money.

Bent was probably already being courted by young Evan Henry Thomas, a recent arrival of mysterious, and possibly dubious, background. It is possible he arrived under a false name. Thomas fancied himself as a litterateur. He had already had some poetry published in the Gazette, professed a knowledge of both the classics and stenography, and was in need of a somewhat better job than he currently had assisting his wife with the Cat and Fiddle pub and selling pastry puffs as a sideline.

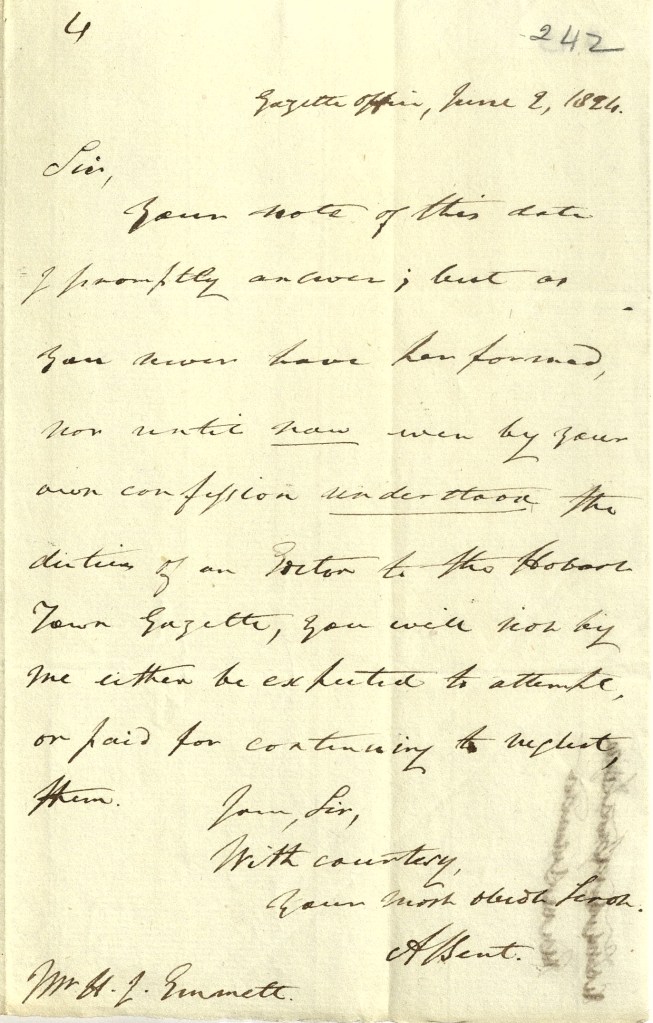

On Saturday 29 May, Bent informed Emmett that he had been offered the services of ‘a gentleman’ (reading between the lines one sees Thomas offering to do two jobs for the price of one) and was about to give him Emmett’s job. Emmett, having received his original appointment from Sorell, refused to budge unless instructed to do so by Arthur. When a few days later he finally offered to do the court reporting if Bent paid him extra he hit a raw nerve. The printing office was short-handed that week. After a drunken fight on pay day two of Bent’s convict workmen were out of action—one dead and the other in custody charged with manslaughter. These circumstances were unlikely to have improved the printer’s temper. He dashed off a withering, if not altogether grammatical response.

Bent had been in the habit of consulting regularly with Emmett on matter for the paper during each week and submitting the final proofs for censorship on Friday morning. During their testy exchange of notes Bent did not visit Emmett at all, and on publication day, as the clock approached two p. m. and there was still no sign of the printer, Emmett learned from the Government bookbinder that several proofs had already been struck off and Bent was correcting them himself. He concluded that the proofs had been deliberately withheld and wrote a note of complaint to Arthur.

Arthur’s reaction

Arthur, unable to find any documentation about the nature of Bent’s appointment, approached his predecessor William Sorell, who was still in the colony, for information. Sorell could not help much but opined that Bent’s action seemed completely out of character, and the man he wished to appoint, stenographic accomplishments notwithstanding, was a most unsuitable person to edit the ‘Government Gazette’. He must have known more about Thomas than we do today. Bent, too, applied to Sorell, in an attempt to justify his actions. He was sent away with a flea in his ear, Sorell hoping that he would come to his senses and place himself ‘in his proper station’ the following morning.

For Arthur, the idea of an unregulated newspaper in a convict colony was unthinkable, especially if its printer was an ex-burglar whose brother was still in bondage in Hobart. According to Arthur Bent’s presumptuous behaviour seemed to indicate he had forgotten the ‘condition’ in which he arrived in the colony and the great indulges he had received from government. Realising he would have to do something to prevent the Gazette coming to a complete standstill, Arthur, in a great rush, applied to his superior, Governor Brisbane, asking him to pass a law requiring newspapers to be licenced. The Attorney General in Hobart, J. T. Gellibrand, new on the job like many of the other players in this drama, drew up a draft Act to send off to Sydney.

Bent must have been told that, unless he accepted government oversight, no licence would be granted to him. He stubbornly refused to buckle.

Brisbane showed Arthur’s letter to Chief Justice Forbes, who opined merely that as the warrant for the new Legislative Council was not yet in place, Governor Brisbane was not in any position to make any laws. Brisbane consulted his Attorney-General, Saxe Bannister, whose advice was exactly the same. Bannister, though, appears to have gone considerably further. By his own later statement, he wrote a long opinion on the question of restricting the press, specifically addressing question of a licence and the situation in Hobart, and concluding that in neither colony would the public peace be at risk from the existence of an unrestrained press. Bannister later characterized himself as always endeavouring to be ‘a firm friend to the liberty of the press’.

Interested observers

On the very day Arthur was writing his instructions to Gellibrand to formulate a new newspaper licensing law, the ship Alfred arrived in the Derwent from London for a short stopover on its way to Sydney. Among the passengers were Wentworth and Wardell who, while their printing press bobbed about on the river, would have observed unfolding events with great interest. We do not know if they met Bent, or inspected his new printing office, but they surely knew what he had done, and, as it was impossible to keep a secret in Hobart Town, they surely also knew of Arthur’s plans for a newspaper licence and of Gellibrand’s role in the business.

They were probably furious as, if Brisbane complied, this could seriously impact their own plans to start an independent newspaper in Sydney. They were not present when Bent made his first move, but may well, canny lawyers as they were, have offered the little printer some useful advice on strategy.

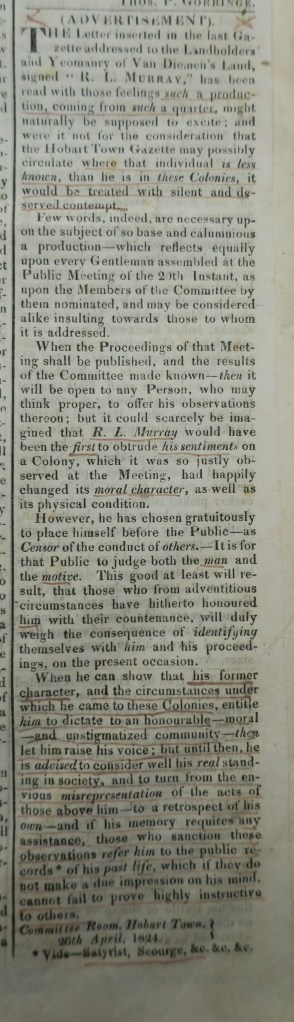

Bent—described by a contemporary as ‘a simple man’—was obviously getting some good legal advice from somewhere, and his next move was far too sophisticated for him to have thought up unaided. It is equally possible that the idea originated with the legally smart Murray, who, as it happens, was intimate with Wentworth’s father D’Arcy. Murray was transported to Sydney, and also knew young William Wentworth briefly before he went to England in 1816. He doubtless spent considerable time socializing with the duo while they were in town. They probably all laughed at Thomas’s first gushingly pretentious editorial in which he invoked shining beacons, sacred sentinels, winnowers of chaff and other polysyllabic nonsense.

Appeal to Governor Brisbane

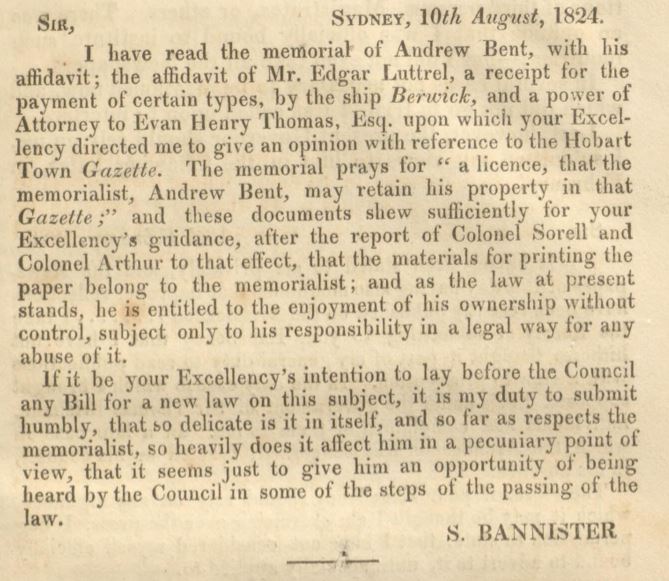

A week or so after the Alfred departed Thomas announced he was going to Sydney for a brief period. He went as Bent’s ambassador, bearing a power of attorney, receipts, and affidavits testifying that Bent owned the paper. One of these, from Edgar Luttrell, was later reprinted in Bent’s paper. These documents accompanied a memorial from Bent praying for a licence so that he might retain his property in the newspaper. Staying, doubtless at Bent’s expense, at the Sydney Hotel, and, if Robert Howe’s waspish portrayal is any guide, cutting a ridiculous figure as a puffed up bragging blatherskite, Thomas nonetheless did his work efficiently. Within a few days Brisbane had received the papers, referred them to his Attorney General and received Bannister’s advice.

Saxe Bannister

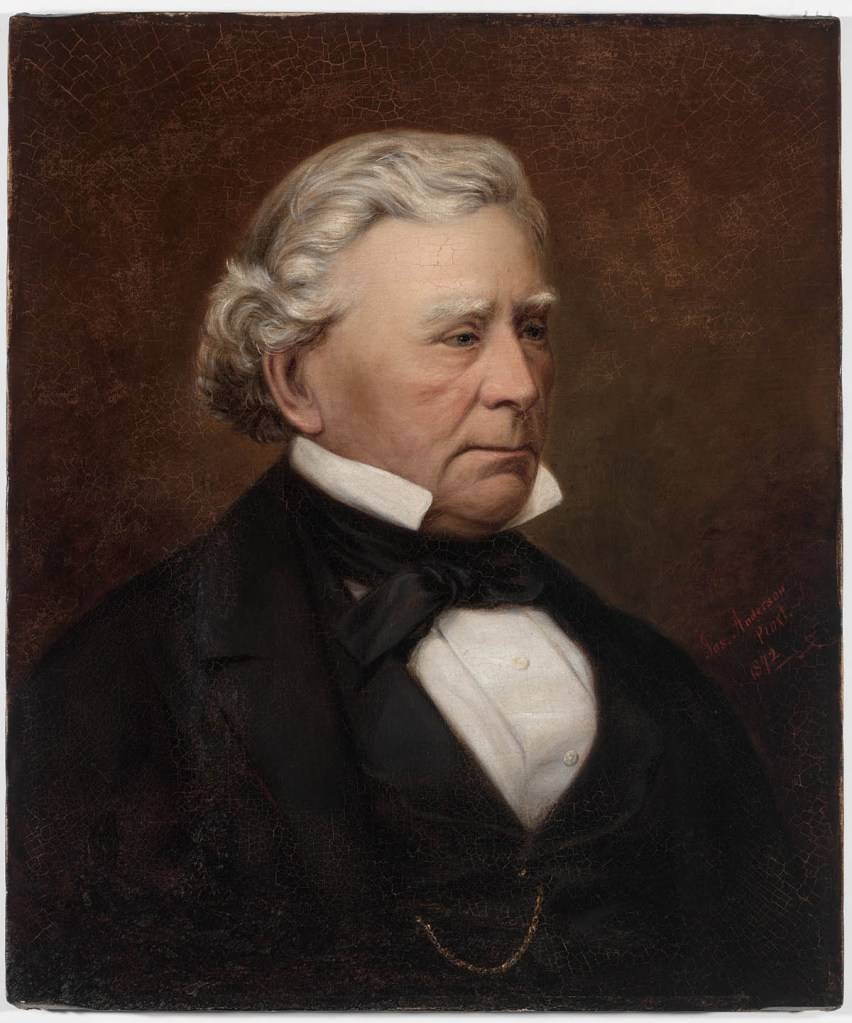

Bannister had also passed through Hobart on his way to Sydney in March 1824. He had a short-lived and rather chequered career as first Attorney-General of New South Wales, departing in high dudgeon in 1826 when his resignation, tendered in bluff, was all too eagerly accepted.

Brisbane’s successor as Governor, Ralph Darling, thought Bannister was mad. Chief Justice Forbes agreed, noting also that Bannister had been derelict in his duty as Attorney-General by failing to prosecute the publishers of libels in the papers, which allowed the liberated press to get completely out of hand.

Bannister has generally received pretty short shrift from historians although Alan Atkinson considers him to be one of the few true intellectuals in early Sydney, noting his enlightened attitudes towards education and the colony’s First Nations peoples. Bannister developed a life-long obsession with what he regarded as unfair treatment in New South Wales. On his way back to England he published a self-justificatory book in Cape Town, in which he briefly wrote about his belief in the value of a free press and reproduced the letter of advice on Bent’s case which he had written to Brisbane.

Although there were some in Hobart who later thought Brisbane had the wool pulled over his eyes about Bent’s ownership of the paper, for Bannister Bent’s ownership of the EQUIPMENT appeared to be the decisive factor (as it was later in Robert Howe’s case).

Vindication

News of Bent’s victory first appeared in the Sydney Gazette on 26 August – not as a formal government notice, but a news report which probably came directly to Robert Howe from an over-excited Thomas. Howe and Bent knew each other, Howe having spent some months in Hobart in 1820. With shared experiences and challenges as colonial printers they had formed a bond of sorts and Howe’s remarks were supportive. ‘It is with feelings of pride and satisfaction we inform the Public, that His EXCELLENCY was pleased to consider Mr. Bent’s claim to publish his said Paper, on his own account, completely indisputable.’

Thomas returned to Hobart ‘puffed with glory’ and in his jubilation immediately made a big mistake. Bent’s Gazette of 8 October reprinted the article from the Sydney Gazette in full . The added commentary celebrated the victory of an ‘outraged weak one’ against a ‘Gideonite of tyranny’. Nobody quite understood what was meant by this mixed metaphor, but it was obviously directed at Arthur and meant as an insult.

Eventually Bent had opportunity to ponder the wisdom of allowing his editor to write this (although he probably agreed with the sentiment) from within the confines of the Murray Street gaol.

At the time though, Arthur, who had determined to no longer mix himself up with Bent, was prepared to make some allowance for over excited feelings and rejected Gellibrand’s advice to prosecute the printer, concentrating instead on finding another means of printing the government notices—easier said than done in the Hobart Town of 1824. Meanwhile Thomas outdid himself in gushing lyricism when the first copies of the Australian appeared in Hobart.

The hour that gives existence in a British Colony to a Free Press, requires not the aid of our feeble pen to extol its worth, or magnify its importance. That hour is pregnant with the embrio virtues of countless worthies yet unborn. And those who love light rather than darkness, must worship it as the dawn of mental glory

Fallout

Until the middle of 1825 Arthur found himself completely at the mercy of Bent’s newly liberated newspaper. Editor Thomas, correspondent Murray (writing anonymously as ‘A Colonist’ in letters more redolent of personal malice than fair political commentary) and others soon began to snipe at Arthur and his officials. Before long Murray and freedom of the press were being toasted at public dinners, Thomas also lapping up the adulation. As early as January 1825 young William Parramore, writing to his fiancée, noted how the printer ‘threw off the shackles of the censorship 9 months ago and boldly dismissed the Govt. editor.’

The printer being in possession of the only type in the island, Govt. have no alternative but to submit tamely to publish the Govt. notices in his paper until a supply of type can be obtained from England. This printer, a simple man, is now the tool of a coterie composed of the most depraved characters, and mischievous because there are among them men of talent.

Parramore identified Murray as the ringleader.

By the middle of 1825 Arthur had found two men to jointly replace Bent as Government Printer. They were Dr. James Ross and young George Terry Howe, half-brother to Robert, who had commenced a newspaper at Launceston earlier in the year. Bent was sacked, convicted of criminal libel, fined and imprisoned for six months. Bent and Thomas had an acrimonious parting of the ways and Murray became Bent’s editor. The attacks on Arthur continued apace in Bent’s paper, which was renamed the Colonial Times, after the new Government Printers appropriated the title Hobart Town Gazette.

The press in the Australian penal colonies was now more free than in Britain. Governor Brisbane had been serenely confident that no harm would result from his decision but, having perused some colonial newspapers (probably copies of the Australian) his masters in London were horrified. When Brisbane’s replacement, Ralph Darling, came out (they all travelled via Hobart) he bore a despatch from Lord Bathurst instructing the colonial governors to impose restrictions on newspapers similar to those existing in England, and if local circumstances justified it, a licence requirement as well.

With Van Diemen’s Land now independent of New South Wales, this legislation was enacted in Hobart in October 1827, specifically to counteract the ‘baneful influence’ of Bent’s Colonial Times. Chief Justice Pedder had no difficulty certifying the proposed legislation as not repugnant to English law. But Justice Forbes in Sydney refused to certify the licence provision, which he strongly suspected had originated from Colonel Arthur in the first place. Under Arthur’s newspaper law, Bent was, predictably, denied a licence, being described as ‘a dangerous and unsafe person to be intrusted with…a public press, more particularly in a penal colony, where the due management and discipline of the convicts demand the utmost care and vigilance’. Arthur was later instructed to rescind the licence provisions following a change in government in England and lobbying from Bent’s supporters. This was a pyrrhic victory for Bent, as his business was already in serious decline.

The opposition press made Arthur’s life a misery in the mid-1820s and again in the 1830s as attacks intensified and some colonists began to demand Arthur’s recall. Governor Darling in Sydney had a pretty rough time of it too. Newspapers in both colonies became allied with campaigns for trial by jury and representative government as increasing numbers of free settlers, all too keen to take advantage of free land and convict labour, also demanded civil rights.

Bent’s Motivation

Trying to establish the motivation for Bent’s bold and risky move has occupied much of our research time. We still have no definitive answers, although the situation would appear to be far more complex than suggested directly by the trail of correspondence between Bent and Emmett which was first examined by Joan Woodberry in the 1960s.

There were obviously multiple factors at play which may or may not have been interconnected other than by their timing. At the very least Bent was asserting his right to hire and fire his own staff and get value for money. His memorial to Brisbane, as well as a letter which appeared in a London paper, would seem to suggest that his primary motivation was to protect the heavy investment he had made in his newspaper business and his right to earn a living at his trade. He was undoubtedly apprehensive about his future under the new administration. Everybody knew that in a post-Bigge environment emancipists could expect less favourable treatment and there even seemed to be a rumour going around that Bent might lose his job.

But Bent’s ‘contumacious’ move, according to Sorell, was completely out character. The printer had previously always been very ‘humble’—i.e. he knew his place and did as he was told. Arthur believed, and later asserted, that a party had formed against him before he even stepped off the boat. He called them ‘Mr. Sorell’s friends’. He also observed, later, that the printer had long been forming new connections.

So perhaps an important question, bearing in mind how Bent’s paper was later used to attack Arthur and his administration and knowing who was chiefly involved in that, is whether there was a political aspect to these events. Parramore’s description suggests that there might have been. To the extent that Bent’s move could be seen as a pre-emptive strike against the new governor, the unsophisticated printer was unlikely to have been acting alone. He may have been influenced or even manipulated by others.

The most likely person to have been behind it, although not the only one, was Robert Lathrop Murray—the acquaintance of D’Arcy Wentworth mentioned above. Murray was a former army officer who had been transported for bigamy in 1815, and came to Hobart from Sydney after he was free. Murray loathed Arthur (the feeling was mutual), and became chief gadfly in the attacks which later appeared in Bent’s paper. He eventually became Bent’s editor. Arthur described him as ‘the most able and wicked man ever sent out to these colonies’.

Murray had exactly the kind of political nous and journalistic experience (from his former association with radical newspapers in London) to know how disruptive an opposition newspaper could be. Historian R. W. Giblin described Murray as ‘dark and slippery’. He was a master player of the double game for whom the personal and the political were often inseparable. Murray’s previously lucrative work as a special pleader in the Lieutenant Governor’s Court had dried up with the establishment of the Supreme Court, so he probably already coveted the editorship of the only newspaper in town. He desperately needed to control the public narrative about his character (and judging by Thomas’s brief report of the libel trial in the Gazette of 18 June he succeeded). And, as Arthur was soon to find out, Murray was a very dangerous man when crossed. From what we know about what was (and was not) published in the newspaper during the independence controversy he had good reason to wish to be revenged on Emmett. Bent, an unsophisticated tradesman imbued with rather naïve idealism about the value of an independent newspaper, would have been easy prey to Murray’s forceful personality and gift of the gab.

Another man who became closely associated with Bent’s paper was merchant Anthony Fenn Kemp. Kemp, formerly of the NSW Corps, and pithily described by David Marr as ‘one of the bad men of early Australia’, was a thorn in the side of Lieutenant Governors Davey, Sorell and Arthur in turn and was chairman of Hobart’s first bank. At one of Bent’s libel trials he denied having a pecuniary interest in the paper. It was interesting that the question must have been put to him.

Conclusion

By October 1824 the time was ripe for the establishment of an independent press in Sydney. There had been sporadic discussion for a couple of years about the desirability of a second newspaper. Wentworth and Wardell were already on their way out, Wentworth having, in the 1824 edition of his book, A Statistical Account of the British Settlements in Australasia, written that

an independent paper… which may serve to point out the rising interests of the colonists and become the organ of their grievance and rights, their wishes and wants–is highly necessary, and, it is to be hoped, will speedily be set on foot.

Saxe Bannister already held a firm view on the benefits of a free press, and had also decided, on the basis of a libel prosecution of Robert Howe shortly after Bannister’s arrival, that the censorship in New South Wales no longer had any teeth. Nonetheless his having already considered Arthur’s licence proposal and Bent’s petition before the decision on censorship of the Sydney Gazette was made, meant the outcome was a foregone conclusion.

Perhaps we should allow Andrew Bent to have the last word. This letter, written on 23 October 1824, soon after Thomas returned from Sydney, appeared in London’s Evening Mail on 4 May 1825, having been sent to one of Bent’s newspaper connections in England. Perhaps it is disingenuous, and in the light of subsequent events the last sentence could be characterised as ‘famous last words’, but it is written from the heart.

Notwithstanding all my exertions for so many years, and the great expense I have been at in establishing the Gazette and the business, yet an attempt has been made to crush me just as I was raising my head in the world. A person high in office, soon after his arrival in this country from England, made an attempt to bereave me entirely of my paper, as well as my business, although I instituted the Hobart-town Gazette at my own expense. I was told that in consequence of my being once in an humble station of life, I should not any longer be the proprietor and editor of the paper actually belonging to me, but that I might remain the Government printer. Without delay, I sent my assistant editor to Sydney, a distance of 800 miles from hence, to lay the particulars of the case before His Excellency Sir Thomas Brisbane, who proved, as I anticipated he would, my best friend… I came off victorious. His Excellency has declared, and has authorized the publication of a statement to that effect in the Sydney Gazette, that he ‘considers my claim to publish the paper on my own account completely indisputable.’ I need not tell you the alteration this has made in the system of conducting my paper. It of course breathes a pure spirit of independence; but while it protects the rights, the liberties, and the happiness of the human race, it will at the same time promote the views of the Colonial Government, without entering into any political or religious controversy.

Further reading:

Joan Woodberry. Andrew Bent and the Freedom of the Press in Van Diemen’s Land. Hobart, Fuller’s Bookshop, 1972.

E. Morris Miller. Pressmen and governors. Sydney University Press, 1973. (Probably still the best source on Murray and Thomas, although, in my view, overly generous to both)

Thanks for this piece on Andrew Bent. I dare say you know that ex-convict James Austin and Andrew Bent reached agreement on the sale of the newspaper to James but it was overturned by Gov. Arthur (a nasty piece of work). James Austin brought his nephews and nieces to VDL, including my g g grandfather, also James.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done Sally! Great article as always on Andrew Bent’s fight for freedom of the press.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Sally, Thank you for another fascinating chapter in the Andrew Bent story, Best wishes, Eve Almond >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sally for another insightful look at the trials and tribulations of an ancestor.

Andrew Hall

LikeLike